‘The Still Alarm’ parodies Brits’ stereotypical ‘stiff upper lip’

Confusions opened tonight on the Alliance for the Arts’ GreenMarket stage. It’s a medley of three one-act plays. The first is droll farce titled The Still Alarm. A period piece that playwright George S. Kauffman first copyrighted in 1925 in the aftermath of World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic, it parodies the Brits’ global reputation as unflappable blokes who remain cool and nonplussed in the face

Confusions opened tonight on the Alliance for the Arts’ GreenMarket stage. It’s a medley of three one-act plays. The first is droll farce titled The Still Alarm. A period piece that playwright George S. Kauffman first copyrighted in 1925 in the aftermath of World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic, it parodies the Brits’ global reputation as unflappable blokes who remain cool and nonplussed in the face  of even the most dire of adversities.

of even the most dire of adversities.

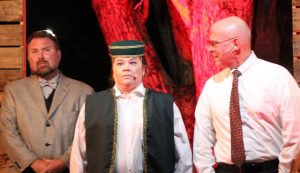

Put simply enough, The Still Alarm depicts two businessmen, played by Rob Green and Thomas Marsh, who maintain their nonchalance and humor in spite of the fact that the hotel in which they are staying is  on fire and in danger of burning to the ground. Even the firefighters who arrive in their 11th-floor room seem unfazed by their mounting peril, as signaled by the heat radiating from the floor beneath their feet as the trusses inch inexorably toward their flash point.

on fire and in danger of burning to the ground. Even the firefighters who arrive in their 11th-floor room seem unfazed by their mounting peril, as signaled by the heat radiating from the floor beneath their feet as the trusses inch inexorably toward their flash point.

Farce is a very difficult type of comedy to do well. It takes capable  character actors to convincingly portray believable chaps who are caught up in a situation that is outrageously surreal. Green and Marsh are up to the challenge, which is all the more formidable because they’re given a script that compels them to evince an attitude and bearing that’s uncommon, if not abhorrent, to an American audience, which would react under similar circumstances with one part gallows humor and two parts unbridled hysteria. Of course, the proper English accents that Green and Marsh employ help bridge this gap.

character actors to convincingly portray believable chaps who are caught up in a situation that is outrageously surreal. Green and Marsh are up to the challenge, which is all the more formidable because they’re given a script that compels them to evince an attitude and bearing that’s uncommon, if not abhorrent, to an American audience, which would react under similar circumstances with one part gallows humor and two parts unbridled hysteria. Of course, the proper English accents that Green and Marsh employ help bridge this gap.  But more, these veteran actors infuse their characters with an endearing quality that enables us to see ourselves in their plight, blissfully ignorant of their apparent impending doom. Would that we all could exhibit such a degree of dignity should we ever find ourselves in mortal jeopardy!

But more, these veteran actors infuse their characters with an endearing quality that enables us to see ourselves in their plight, blissfully ignorant of their apparent impending doom. Would that we all could exhibit such a degree of dignity should we ever find ourselves in mortal jeopardy!

The same can also be said for the tertiary characters in this one-act play. Lucy Sundby plays the bellgirl, who knocks on their door to inform them of the fire and recommend that they consider vacating their room  and fleeing the building. Lemec Bernard and Sonya McCarter play the firefighters sent to rescue Green and Marsh’s characters, and they gleefully augment Kauffman’s parody of British imperturbability by breaking out a violin and playing music in the tradition of the musicians on board the Titanic as floor beneath their blistering feet gets hotter and hotter and hotter.

and fleeing the building. Lemec Bernard and Sonya McCarter play the firefighters sent to rescue Green and Marsh’s characters, and they gleefully augment Kauffman’s parody of British imperturbability by breaking out a violin and playing music in the tradition of the musicians on board the Titanic as floor beneath their blistering feet gets hotter and hotter and hotter.

The Still  Alarm clearly lampoons Brits’ penchant for soldiering through any crisis or catastrophe with aplomb and Bond-like detachment, and to provide context, Kauffman is taking issue with the British plays of his day that were full of stiff characters who interacted with one another in a polite, formal manner no matter the situation. But Brits’ so-called stiff upper lip was actually an American invention, appearing in a number of publications dating back as far as 1815 and including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1952 masterwork,

Alarm clearly lampoons Brits’ penchant for soldiering through any crisis or catastrophe with aplomb and Bond-like detachment, and to provide context, Kauffman is taking issue with the British plays of his day that were full of stiff characters who interacted with one another in a polite, formal manner no matter the situation. But Brits’ so-called stiff upper lip was actually an American invention, appearing in a number of publications dating back as far as 1815 and including Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1952 masterwork,  Uncle Tom’s Cabin. However, it was the 1937 movie Damsel in Distress (starring George Burns, Gracie Allen and Fred Astaire) that ascribed the term exclusively to the good folks living across the pond.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin. However, it was the 1937 movie Damsel in Distress (starring George Burns, Gracie Allen and Fred Astaire) that ascribed the term exclusively to the good folks living across the pond.

Somewhere along the way, the British appropriated the sobriquet and claimed it as their own, but this was years after George Kauffman penned The Still Alarm. So it was prescient if nothing else that Kauffman’s  characters display the fortitude, stoicism and dry wit in the face of adversity that we now associate with Brits as a matter of national character and pride.

characters display the fortitude, stoicism and dry wit in the face of adversity that we now associate with Brits as a matter of national character and pride.

All that aside, The Silent Alarm is a very funny piece of theater in a Monty Python sort of way. Rob Green and Thomas Marsh won’t have you rolling in the aisles or on the GreenMarket lawn, but they will trigger an unending string of chuckles, chortles and  deep-throated guffaws. It’s a great kick-off to the trio of plays that Director Bill Taylor has subsumed under Confusions and really sets the table for what follows in Between Mouthfuls.

deep-throated guffaws. It’s a great kick-off to the trio of plays that Director Bill Taylor has subsumed under Confusions and really sets the table for what follows in Between Mouthfuls.

January 21, 2021.

N.B.: On a serious note, hotel fires at the time Kauffman wrote  The Still Alarm were characteristically deadly due to the fact that stairwells at this time were not protected. “Once a fire reached the stairwell,” notes former Fort Myers Fire Chief Richard T. Chappelle, “it was all over because that was often the only means of escape.” Such was the case in the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911. The building had four elevators and two staircases. Unfortunately, only one of the elevators was working at the time of the fire, and one staircase

The Still Alarm were characteristically deadly due to the fact that stairwells at this time were not protected. “Once a fire reached the stairwell,” notes former Fort Myers Fire Chief Richard T. Chappelle, “it was all over because that was often the only means of escape.” Such was the case in the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911. The building had four elevators and two staircases. Unfortunately, only one of the elevators was working at the time of the fire, and one staircase  was locked to prevent stealing while the other only opened inward. As a result, 145 workers lost their lives, with 36 perishing in the elevator shaft and 58 more electing to plunge to their deaths rather than burning to death. But the hotel in A Still Alarm was probably patterned after the Windsor Hotel East, which caught fire in the midst of New York City’s St. Patrick’s Day parade. All seven floors were engulfed by the fire, and while some guests were saved by falling into nets or clambering down ladders, 86 people

was locked to prevent stealing while the other only opened inward. As a result, 145 workers lost their lives, with 36 perishing in the elevator shaft and 58 more electing to plunge to their deaths rather than burning to death. But the hotel in A Still Alarm was probably patterned after the Windsor Hotel East, which caught fire in the midst of New York City’s St. Patrick’s Day parade. All seven floors were engulfed by the fire, and while some guests were saved by falling into nets or clambering down ladders, 86 people  died (although only 45 bodies could be recovered from the smoldering ruins).

died (although only 45 bodies could be recovered from the smoldering ruins).

As a point in fact, Rob Green and Thomas Marsh’s characters do the very thing that will likely get you killed in a fire or other emergency. Once again, former Fort Myers Fire Chief Richard Chappelle provides the critical observation: “In fires, terrorist attacks and other emergencies, it’s the people who don’t hesitate who most often survive. Inasmuch as most fires occur between midnight and 3:00 a.m., the key to surviving a hotel fire is familiarizing yourself with the hotel’s posted evacuation plan. Chief Chappelle lays this out in clear, easy-to-comprehend steps  which you can find on pages 51 and 52 of the author’s book Epic Fires of Fort Myers, How a Series of Early Fires Influenced the Town’s Development.

which you can find on pages 51 and 52 of the author’s book Epic Fires of Fort Myers, How a Series of Early Fires Influenced the Town’s Development.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.