Courageous direction, inspired acting draw out convoluted themes of Mamet’s ‘Race’

Lab Theater of Florida prides itself on bringing provocative, edgy plays to the stage. Within that penumbra, Artistic Director Annette Trossbach and the Lab Board (gratefully) gravitate toward perspective-bending productions in which the “reality” perceived by the audience is filtered through the lens of the play’s principal character. In Sarah Ruhl’s How to Transcend a Happy Marriage that reality was shaped by Trossbach’s own character, George, who suffered from adaptive/maladaptive dissociative disorder. In Arthur Kopit’s Wings,

Lab Theater of Florida prides itself on bringing provocative, edgy plays to the stage. Within that penumbra, Artistic Director Annette Trossbach and the Lab Board (gratefully) gravitate toward perspective-bending productions in which the “reality” perceived by the audience is filtered through the lens of the play’s principal character. In Sarah Ruhl’s How to Transcend a Happy Marriage that reality was shaped by Trossbach’s own character, George, who suffered from adaptive/maladaptive dissociative disorder. In Arthur Kopit’s Wings,  the audience experiences the stroke that topples Cindy Chase’s Emily Stilson. In Botticelli in the Fire, the historical record and personalities of Leonardo da Vinci, Lorenzo de Medici and Clarice Orsini are distorted by Sandro Botticelli’s desire to repair his reputation for future generations. And in David Mamet’s Race,

the audience experiences the stroke that topples Cindy Chase’s Emily Stilson. In Botticelli in the Fire, the historical record and personalities of Leonardo da Vinci, Lorenzo de Medici and Clarice Orsini are distorted by Sandro Botticelli’s desire to repair his reputation for future generations. And in David Mamet’s Race,  it’s lawyer Jack Lawson who colors our perception of the events and other characters who interact in his minimalist conference room.

it’s lawyer Jack Lawson who colors our perception of the events and other characters who interact in his minimalist conference room.

Shows like these insinuate themselves in viewers’ mental makeup and emotional psyche in a way few others can. Just look at The Father, which garnered Best Motion Picture nominations from the Academy Awards, Golden Globes, BAFTA and Screen Actors Guild and resulted in Oscars for Anthony Hopkins (Best Actor) and Christopher Hampton (Best  Adapted Screenplay).

Adapted Screenplay).

But here, we’re talking David Mamet. The storied playwright is not content to merely take liberties with point of view (POV). He makes each of his four characters metaphors for broad segments of society as considered from within the framework of the white power structure that controls (at least presently) our political and social institutions, including the criminal justice system.

Crafting characters who are stand-ins for wide swaths of American society entails certain compromises. In Race, Mamet has sacrificed some of the realism and authenticity that made the characters in shows like Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo and Oleanna so compelling. Here, the wants, fears and motivations of the lawyers and their putative client seem strained, even absurd. And so it was a tall order for Director Sonya McCarter

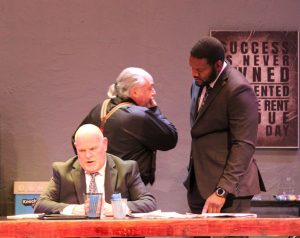

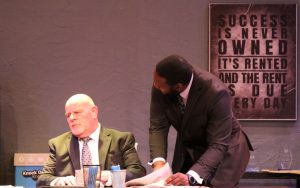

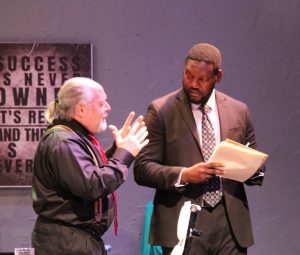

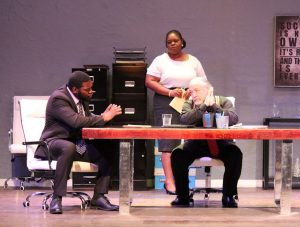

Crafting characters who are stand-ins for wide swaths of American society entails certain compromises. In Race, Mamet has sacrificed some of the realism and authenticity that made the characters in shows like Glengarry Glen Ross, American Buffalo and Oleanna so compelling. Here, the wants, fears and motivations of the lawyers and their putative client seem strained, even absurd. And so it was a tall order for Director Sonya McCarter and her cast to infuse Jack Lawson, Henry Brown, Susan (no last name) and Charles Strickland with the depth and emotionality needed in order to make them believable. But did they ever – thanks to Sonya McCarter’s courageous direction and inspired acting by Brian Linthicum, Lemec Bernard, Michael A. Massari and Cantrella Canady.

and her cast to infuse Jack Lawson, Henry Brown, Susan (no last name) and Charles Strickland with the depth and emotionality needed in order to make them believable. But did they ever – thanks to Sonya McCarter’s courageous direction and inspired acting by Brian Linthicum, Lemec Bernard, Michael A. Massari and Cantrella Canady.

Brian Linthicum portrays Charles Strickland, a billionaire  who has been accused of raping a young black woman. Strickland maintains that he and the woman had been having a consensual affair for some time. In spite of the #metoo and #timesup movements, it remains difficult, if not impossible, to win a conviction in the absence of witnesses, but as it turns out, a preacher and his wife in the adjoining hotel room heard Strickland utter a racial slur as he threw his accuser down on the bed.

who has been accused of raping a young black woman. Strickland maintains that he and the woman had been having a consensual affair for some time. In spite of the #metoo and #timesup movements, it remains difficult, if not impossible, to win a conviction in the absence of witnesses, but as it turns out, a preacher and his wife in the adjoining hotel room heard Strickland utter a racial slur as he threw his accuser down on the bed.  And with that, Jack Lawson concludes that Strickland’s case is not about rape, but race, for which there can be no defense.

And with that, Jack Lawson concludes that Strickland’s case is not about rape, but race, for which there can be no defense.

Strickland comes across as both hapless and naïve. He’s convinced that he’ll be vindicated by the criminal justice system or, barring that, the media will help him restore his reputation. But what he’s indicted for in  Mamet’s world isn’t misogyny. It’s white privilege, implicit bias and systemic racism.

Mamet’s world isn’t misogyny. It’s white privilege, implicit bias and systemic racism.

Charles Strickland is so obtuse that he doesn’t realize that the racial slur played a role, perhaps the pivotal role in his accuser bringing rape charges against him until he’s confronted by the sad truth that his African-American bestie from college has held a grudge against him for more than a quarter of a century  because of yet another racial slur that Strickland made while on a trip to Jamaica. In fact, Charles Strickland is so self-absorbed and unaware that until that very moment, he never saw himself as racist at all.

because of yet another racial slur that Strickland made while on a trip to Jamaica. In fact, Charles Strickland is so self-absorbed and unaware that until that very moment, he never saw himself as racist at all.

Although Mamet doesn’t delve into his background, Strickland no doubt has black friends and employees. He probably has a legion of African-American musicians and entertainers in his CD collection.  He may have even looked back on Jim Crow with disdain and embarrassment. When he’s looked in the mirror each morning as he shaved, not once did he ever see a racist staring back at him. But once Charles accepts the bitter truth that he harbors racist beliefs and views, he feels shame and a consuming need for atonement, which Linthicum convincingly conveys. From that instant in the play, Linthicum

He may have even looked back on Jim Crow with disdain and embarrassment. When he’s looked in the mirror each morning as he shaved, not once did he ever see a racist staring back at him. But once Charles accepts the bitter truth that he harbors racist beliefs and views, he feels shame and a consuming need for atonement, which Linthicum convincingly conveys. From that instant in the play, Linthicum  becomes the personification of guilt and humiliation. His remorse is almost palpable.

becomes the personification of guilt and humiliation. His remorse is almost palpable.

Of course, what doesn’t make sense is the billionaire’s desire to go public with his guilt. To confess. Any similarly-situated man of wealth and power would have  his lawyers pay off his accuser or find people from her past that will attack her morals or credibility. At worst, he’d cop to a lesser plea knowing that in today’s criminal justice system a wealthy older white guy wouldn’t serve a day in prison. Probation for someone like Charles Strickland would be a piece of cake.

his lawyers pay off his accuser or find people from her past that will attack her morals or credibility. At worst, he’d cop to a lesser plea knowing that in today’s criminal justice system a wealthy older white guy wouldn’t serve a day in prison. Probation for someone like Charles Strickland would be a piece of cake.

But Mamet is not  trying to craft a credible character. Strickland is a metaphor for that broad segment of white Americana that have convinced themselves they don’t have a racist bone in their entire body. And like Charles Strickland, they resort to the media in the vain attempt to convince everyone else of their racial equanimity.

trying to craft a credible character. Strickland is a metaphor for that broad segment of white Americana that have convinced themselves they don’t have a racist bone in their entire body. And like Charles Strickland, they resort to the media in the vain attempt to convince everyone else of their racial equanimity.

Don’t take Mamet’s word for that. Just look at Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and other social media outlets over the past year or more. In an ongoing effort to convince others of their enlightenment,  ten of thousands of white Americans have flocked to their preferred social media platform to profess that “all lives matter;” that if you have to produce a picture ID to get a COVID vaccine then, ipso facto, why shouldn’t you have to produce one to vote; that white privilege is a myth because they’ve had to work for every damn thing they’ve ever achieved. Hell, even Senator Tim Scott admits that “America is not a racist country,” and he should know because, after all,

ten of thousands of white Americans have flocked to their preferred social media platform to profess that “all lives matter;” that if you have to produce a picture ID to get a COVID vaccine then, ipso facto, why shouldn’t you have to produce one to vote; that white privilege is a myth because they’ve had to work for every damn thing they’ve ever achieved. Hell, even Senator Tim Scott admits that “America is not a racist country,” and he should know because, after all,  he’s black!

he’s black!

Heed the words of the Bard: “Methinks thou dost protest too much.”

So while the motivations, intent and actions of Charles Strickland may seem to strain credulity in the confines of Lawson and Brown’s conference room, as a metaphor for the implicit racism lurking, perhaps even lying dormant, within the psyche of many  white Americans, the character makes perfect sense and Linthicum does an exceptional job of drawing out of his character the profound shame, guilt and abject humiliation he experiences at this moment of self-discovery.

white Americans, the character makes perfect sense and Linthicum does an exceptional job of drawing out of his character the profound shame, guilt and abject humiliation he experiences at this moment of self-discovery.

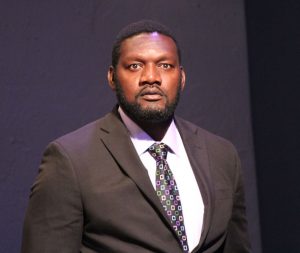

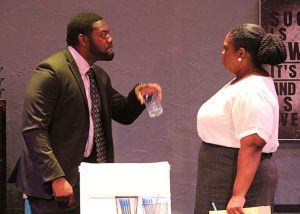

Lemec Bernard burst upon the local theater scene in August Wilson’ Joe Turner’s Come and Gone. He’d previously appeared in The Storms at Home and Mr. Burns: A Post Electric Play, but  colleagues and theater-goers alike recognized in Joe Turner that Lemec was going to cast a formidable presence on our local stages. His subsequent performances have borne that out, but his portrayal of Henry Brown is by far his most nuanced performance to date.

colleagues and theater-goers alike recognized in Joe Turner that Lemec was going to cast a formidable presence on our local stages. His subsequent performances have borne that out, but his portrayal of Henry Brown is by far his most nuanced performance to date.

Bernard’s task was unenviable. Henry Brown comes across as tough, shrewd, driven and combative, qualities clients covet in a criminal defense attorney. But in Mamet-world, Henry Brown represents that segment of the African-American population that is so determined to succeed in white society they shun their more vocal and strident counterparts. In Race, for example, Brown tells his white law partner not to hire Susan, warns him that she’s trouble and refers to her as a “science experiment.”

in a criminal defense attorney. But in Mamet-world, Henry Brown represents that segment of the African-American population that is so determined to succeed in white society they shun their more vocal and strident counterparts. In Race, for example, Brown tells his white law partner not to hire Susan, warns him that she’s trouble and refers to her as a “science experiment.”

Mamet doesn’t give us any background about  Brown or how he and Jack Lawson came to be law partners. Their relationship appears to be strictly business. In fact, in the very first scene Henry admonishes Jack Lawson not to call him brother. Lawson has given him the opportunity to succeed, the means to excel. Their connection is about winning and the money that commands. Nothing more; nothing less.

Brown or how he and Jack Lawson came to be law partners. Their relationship appears to be strictly business. In fact, in the very first scene Henry admonishes Jack Lawson not to call him brother. Lawson has given him the opportunity to succeed, the means to excel. Their connection is about winning and the money that commands. Nothing more; nothing less.  They’re law partners; not friends.

They’re law partners; not friends.

But Brown’s refusal to back Susan in her skirmishes with Lawson opens Bernard’s character to the charge that he’s “acting white.” African-Americans rightfully bristle at this characterization although, to keep it real, “acting white,” “talking white” and “ are sometimes used as pejoratives in the  black community. But blacks well know – and often tire of having to remind white politicians – that African-Americans are not a homogenous demographic. Black people don’t all think alike, act alike or vote alike. They’re every bit as unique and individual as white, Latinx and Asian folks are.

black community. But blacks well know – and often tire of having to remind white politicians – that African-Americans are not a homogenous demographic. Black people don’t all think alike, act alike or vote alike. They’re every bit as unique and individual as white, Latinx and Asian folks are.

Still, there is pressure exerted by white society on all people of color to abandon, if not eschew, their culture and heritage in order to assimilate into white society. But while it may trouble, vex or occasionally  anger some segment of the black community when a person of color seems to stand with whites in derogation of the interests of black people (i.e. “you’re a sellout;” “you’re not black enough”), what emerges from Race is that while the Henry Browns out there may not feel warm and fuzzy about the Jack Lawsons in their lives, they don’t pose a threat to the white power structure that’s ingrained in our political, educational,

anger some segment of the black community when a person of color seems to stand with whites in derogation of the interests of black people (i.e. “you’re a sellout;” “you’re not black enough”), what emerges from Race is that while the Henry Browns out there may not feel warm and fuzzy about the Jack Lawsons in their lives, they don’t pose a threat to the white power structure that’s ingrained in our political, educational,  economic and other institutions.

economic and other institutions.

Poor Lemec Bernard. Henry Brown is probably the least liked and understood character on stage! But his portrayal is nonetheless spot on.

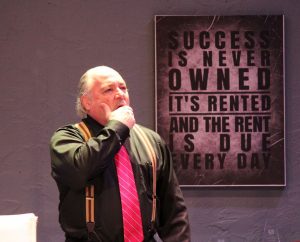

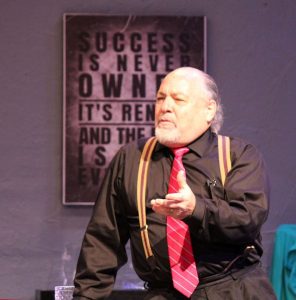

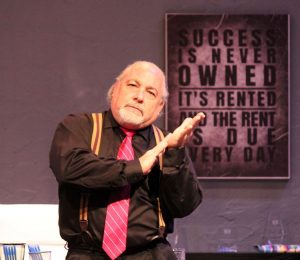

Charles Strickland may be the one accused of racism in the play, but it’s Jack Lawson who’s indicted as a racist by Mamet in this play. With cowboy boots clattering the faux floor of the Lab  Theater stage and his grey hair pulled back into a ponytail, Michael A. Massari does an astonishing job channeling his inner Gerry Spence to portray the arrogant, swashbuckling Jack Lawson. As a former lawyer, I say this with admiration. Massari captures and expertly conveys every attribute we laud and despise when it comes to members of the Bar.

Theater stage and his grey hair pulled back into a ponytail, Michael A. Massari does an astonishing job channeling his inner Gerry Spence to portray the arrogant, swashbuckling Jack Lawson. As a former lawyer, I say this with admiration. Massari captures and expertly conveys every attribute we laud and despise when it comes to members of the Bar.  He preens, he leans, he puts his boots up on the table. He’s the perfect bombastic self-impressed trial lawyer par excellence.

He preens, he leans, he puts his boots up on the table. He’s the perfect bombastic self-impressed trial lawyer par excellence.

Within the contours of the play, Jack Lawson is the penultimate manipulator. He’s constantly angling for the leverage that enables him to get what he wants from the clients, judges, juries and other players who fall within his orbit. But from a metaphorical vantage, Jack Lawson is an unapologetic  stand-in for those in white society who (1) ruthlessly protect the power they wield and (2) continue to treat blacks as chattels, albeit in a less obvious manner than the white plantation owners of yesteryear.

stand-in for those in white society who (1) ruthlessly protect the power they wield and (2) continue to treat blacks as chattels, albeit in a less obvious manner than the white plantation owners of yesteryear.

White privilege, implicit bias and outright bigotry may be manifestations of racism, but what lies at the black heart of racism is power. Racism is a system  by which those in power retain that power by creating preferential access to jobs, business opportunity, education, housing, health, nutrition and the political and legal system in favor of whites and restricting that access to people of color. And as people of color grow in numbers and purchasing power, the white power structure seeks to preserve its position by preventing people of color from entering the country and by restricting POC’s access to the polls through a legion of voter suppression laws and

by which those in power retain that power by creating preferential access to jobs, business opportunity, education, housing, health, nutrition and the political and legal system in favor of whites and restricting that access to people of color. And as people of color grow in numbers and purchasing power, the white power structure seeks to preserve its position by preventing people of color from entering the country and by restricting POC’s access to the polls through a legion of voter suppression laws and  gerrymandered voting districts. Where people of color turn out in massive numbers to exercise the franchise they’ve fought so hard and so long to get, the results are dismissed as the result of voter fraud in communities with large black and Latino populations like Wayne County (Detroit) in Michigan or Fulton County (Atlanta) in Georgia.

gerrymandered voting districts. Where people of color turn out in massive numbers to exercise the franchise they’ve fought so hard and so long to get, the results are dismissed as the result of voter fraud in communities with large black and Latino populations like Wayne County (Detroit) in Michigan or Fulton County (Atlanta) in Georgia.

Jack Lawson knows that race is about power.  He doesn’t hire Susan because he admires her intellect or is color blind. He hires her because she’s potentially an asset, and he thinks he can control her because he has something on her that he can use to blackmail her into doing whatever he wants whenever he wants. Race, in that view, is a more pernicious iteration of John Grisham’s The Firm.

He doesn’t hire Susan because he admires her intellect or is color blind. He hires her because she’s potentially an asset, and he thinks he can control her because he has something on her that he can use to blackmail her into doing whatever he wants whenever he wants. Race, in that view, is a more pernicious iteration of John Grisham’s The Firm.

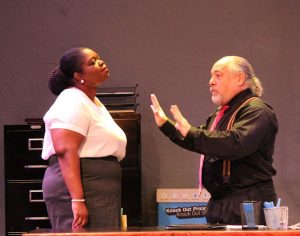

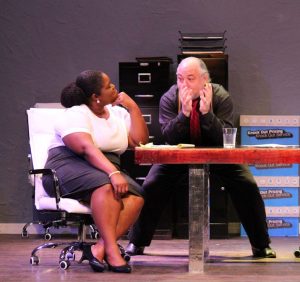

It’s not possible to say enough about Cantrella Canady’s immense talent as an actor. She understands characters at an intuitive, organic level. She’s splendidly acquitted herself in dramas like Ma Rainey,  King Hedley II, A Raisin in the Sun and George Wolfe’s The Colored Museum. But in Race, audiences will see her as never before. In Race, she gets to tap into a new emotional palette. As Susan, she’s deliciously diabolical as she takes on her smug, condescending, smarmy employer and ersatz mentor, a man who represents all that’s wrong in white society.

King Hedley II, A Raisin in the Sun and George Wolfe’s The Colored Museum. But in Race, audiences will see her as never before. In Race, she gets to tap into a new emotional palette. As Susan, she’s deliciously diabolical as she takes on her smug, condescending, smarmy employer and ersatz mentor, a man who represents all that’s wrong in white society.

Without giving away too much, don’t be lulled into  believing that she’s affronted by Lawson asking her to put on a red-sequined dress that he can rip off her in front of the jury. Her problems with Lawson have little to do with misogyny or sex. From within the confines of the play, she sees Lawson for what he is. On a broader basis, Mamet uses her character to express the view that African-Americans can one day, some day, outwit and overturn the white power structure. They’re smart enough, fed up enough, and willing to get into that good trouble that John Lewis espoused. Canady is the perfect actor to underscore this message. If you’re casting for attitude,

believing that she’s affronted by Lawson asking her to put on a red-sequined dress that he can rip off her in front of the jury. Her problems with Lawson have little to do with misogyny or sex. From within the confines of the play, she sees Lawson for what he is. On a broader basis, Mamet uses her character to express the view that African-Americans can one day, some day, outwit and overturn the white power structure. They’re smart enough, fed up enough, and willing to get into that good trouble that John Lewis espoused. Canady is the perfect actor to underscore this message. If you’re casting for attitude,  Cantrella’s the obvious choice.

Cantrella’s the obvious choice.

It’s interesting to note that Mamet wrote Race in 2009. The issues he presaged have only gotten worse. To say that Race is still timely is a gross understatement. If anything, the themes of this play will only become more salient as the entrenched white power structure finds itself under more and more duress as people of color become the majority and assume positions  of authority that once fell solely within the control of older white men.

of authority that once fell solely within the control of older white men.

With all of that said, it bears repeating that the reality we’re given in Race is filtered through the eyes of Jack Lawson and the world view of one David Mamet. While the play provides grist for much-needed frank conversation about race, in the final analysis Race represents the views of an older white playwright’s slant on this all-important  topic.

topic.

Mamet notoriously prohibits theater companies from staging post-performance talkbacks, but it would be a most interesting exercise to see how the characters and story would evolve if Race were ever to be rewritten by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Marcus Gardley or, even better, Suzan-Lori Parks.

May 6, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.