With ‘Shadopia,’ Mariapia Malerba draws attention to endangered species

Fashion designer, visual artist and filmmaker Mariapia Malerba has installed an awe-inspiring and overpowering exhibition of new work in the Capital Gallery in the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center in February. Called Shodopia, the show is comprised of work she’s created with a technique inspired by Shodo.

Fashion designer, visual artist and filmmaker Mariapia Malerba has installed an awe-inspiring and overpowering exhibition of new work in the Capital Gallery in the Sidney & Berne Davis Art Center in February. Called Shodopia, the show is comprised of work she’s created with a technique inspired by Shodo.

Shodo is a  form of calligraphy in which an ink-dipped brush is used to create Chinese kanji and Japanese kana characters. Practitioners are admired for the accuracy of the characters they create, the balance with which they arrange them on the paper, how they shade the ink and, especially, the way they handle the brush while performing the calligraphy.

form of calligraphy in which an ink-dipped brush is used to create Chinese kanji and Japanese kana characters. Practitioners are admired for the accuracy of the characters they create, the balance with which they arrange them on the paper, how they shade the ink and, especially, the way they handle the brush while performing the calligraphy.

The art of Shodo originated in China during the Han dynasty and came to Japan in the sixth century, along with methods for making brushes,  ink and paper. In those days, calligraphy was an essential part of the education of members of noble families. But as time passed, the art spread among the common people. Today Shodo is not just a celebrated and revered art form, but a harmonious and philosophical process that fuses poetry, literature, and painting by possessing rhythm, emotion, aesthetic and spirituality in one unique art form. It’s such an important aspect of Japanese culture

ink and paper. In those days, calligraphy was an essential part of the education of members of noble families. But as time passed, the art spread among the common people. Today Shodo is not just a celebrated and revered art form, but a harmonious and philosophical process that fuses poetry, literature, and painting by possessing rhythm, emotion, aesthetic and spirituality in one unique art form. It’s such an important aspect of Japanese culture  and ideals that it is even introduced to Japanese children as early as elementary school.

and ideals that it is even introduced to Japanese children as early as elementary school.

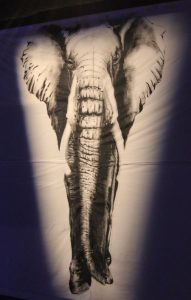

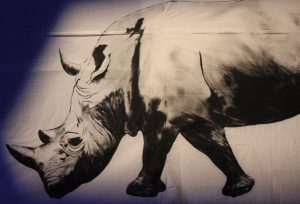

Although Mariapia also employs a brush for the more minute,  detailed aspects of her images, she actually used a broom to paint large swathes of her support, which consists of 208 uninterrupted lineal feet of recycled paper panels taped together into a single “canvas” reminiscent of Bob Rauschenberg’s 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece (1981-98). But unlike that work, Mariapia confined her pallet to various shades of black.

detailed aspects of her images, she actually used a broom to paint large swathes of her support, which consists of 208 uninterrupted lineal feet of recycled paper panels taped together into a single “canvas” reminiscent of Bob Rauschenberg’s 1/4 Mile or 2 Furlong Piece (1981-98). But unlike that work, Mariapia confined her pallet to various shades of black.

The monotone is intentional. It underscores the theme of the imagery stretching down the walls and around the room. A cryptic note greets the viewer when they enter the exhibition space through a fold in a white sheet. “In my dreams I fly like an eagle In my dreams animals speak to me When I am awake nature fills life with beauty and joy.” But these animals are screaming a warning. Each is endangered or facing extinction, a message underscored by the rod and bob of a grandfather clock swinging ominously on the opposing wall.

The monotone is intentional. It underscores the theme of the imagery stretching down the walls and around the room. A cryptic note greets the viewer when they enter the exhibition space through a fold in a white sheet. “In my dreams I fly like an eagle In my dreams animals speak to me When I am awake nature fills life with beauty and joy.” But these animals are screaming a warning. Each is endangered or facing extinction, a message underscored by the rod and bob of a grandfather clock swinging ominously on the opposing wall.

Mariapia’s imagery is astonishing. She infuses the realism of her images with an unmistakable spirituality and kinetic dynamism. She enlists diluted black acrylic in a valiant effort to keep her animals from vanishing as  time inexorably wears on.

time inexorably wears on.

But these animals are vanishing right before our eyes. Ninety-five percent of all elephants have vanished from the planet. Fewer than 400,000 remain. Giraffes are facing a more silent extinction; their numbers have declined by 40 percent to just 97,000, due to habitat loss, hunting and climate-related factors. Fewer than 25,000 rhinos remain, with the last northern white male dying in 2018, and the right whale is down to fewer than 500, their decline linked to ocean warming. The western lowland gorilla is critically endangered due to logging, poaching and even Ebola. Because of ongoing loss of their sea ice habitat resulting from climate change, polar bears are threatened. In fact, 75 percent of bear species face extinction.

And then there’s the bee. Due to colony collapse and other environmental factors, bee populations have been declining with alarming rapidity all around the globe.

And then there’s the bee. Due to colony collapse and other environmental factors, bee populations have been declining with alarming rapidity all around the globe.

In fact, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reports that nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history. Based on a systematic review  of some 15,000 scientific and government sources, the IPBES report is the most comprehensive assessment of its kind to date. Presented in Paris a year ago in May, it notes that 1,000,000 species now face extinction. And the rate of decline is accelerating! But it is still not too late to initiate changes. Nature can still be conserved, restored and used sustainably “through transformative change.”

of some 15,000 scientific and government sources, the IPBES report is the most comprehensive assessment of its kind to date. Presented in Paris a year ago in May, it notes that 1,000,000 species now face extinction. And the rate of decline is accelerating! But it is still not too late to initiate changes. Nature can still be conserved, restored and used sustainably “through transformative change.”

In her installation, Mariapia delivers this clarion call through the symbolism of the raven. They fly and flap around the piece, in a thick black flock on one wall – using ropes to carry off the carcass of an overturned dead whale on another. It’s an inspired, heady choice. From the time of Edgar Allen Poe to the present, ravens express mournful, never-ending remembrance and provide connection to death and the underworld while simultaneously signalling that it’s time to pause and give serious consideration to impending transformation.

In her installation, Mariapia delivers this clarion call through the symbolism of the raven. They fly and flap around the piece, in a thick black flock on one wall – using ropes to carry off the carcass of an overturned dead whale on another. It’s an inspired, heady choice. From the time of Edgar Allen Poe to the present, ravens express mournful, never-ending remembrance and provide connection to death and the underworld while simultaneously signalling that it’s time to pause and give serious consideration to impending transformation.

It is easy, almost inevitable, to get swept up in the lighting, scope and scale of the imagery included in this show. On opening night, the gallery  was full of conversation and chatter. But this exhibition is really meant to be experienced with reverence – in quiet contemplation and respectful reflection. Linger and allow the artist to speak to you through her artwork. If you do, you’ll feel her care, concern and angst. They’re lurking just below the calligraphic surface, waiting to be discovered. But whether you go alone or in a

was full of conversation and chatter. But this exhibition is really meant to be experienced with reverence – in quiet contemplation and respectful reflection. Linger and allow the artist to speak to you through her artwork. If you do, you’ll feel her care, concern and angst. They’re lurking just below the calligraphic surface, waiting to be discovered. But whether you go alone or in a  group, it’s a show you really should see. Go now. Go again. It’s a thought-provoking exhibition.

group, it’s a show you really should see. Go now. Go again. It’s a thought-provoking exhibition.

And if you really want to impress and please the artist, do something to protect these animals and the environment in which they live. All of us can make changes to protect the planet and be better stewards of the world we share with the plant and animal kingdoms. N’est pas?

[Go here to see a 2-minute short film titled The Dancing Shadow on the Rose in which Mariapia demonstrates her newfound art form of Shodopia: You can see that film here.]

February 22, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.