Residents of Louisiana’s Isle de Jean Charles becoming climate change refugees

One of the more impactful documentaries screened at the 3rd Annual Bonita Springs International Film Festival was Before the Flood. Directed by Fisher Stevens, the climate change documentary follows Academy Award-winning actor and U.N. Messenger of Peace Leonardo DiCaprio on a three-year journey during which he interviews individuals from every facet of society in both developing and developed nations to discover what must be done today and in the future to prevent catastrophic disruption of life on our planet. One of the topics discussed in the film is the threat of sea level rise as a consequence of rising temperatures resulting from greenhouse gas emissions.

One of the more impactful documentaries screened at the 3rd Annual Bonita Springs International Film Festival was Before the Flood. Directed by Fisher Stevens, the climate change documentary follows Academy Award-winning actor and U.N. Messenger of Peace Leonardo DiCaprio on a three-year journey during which he interviews individuals from every facet of society in both developing and developed nations to discover what must be done today and in the future to prevent catastrophic disruption of life on our planet. One of the topics discussed in the film is the threat of sea level rise as a consequence of rising temperatures resulting from greenhouse gas emissions.

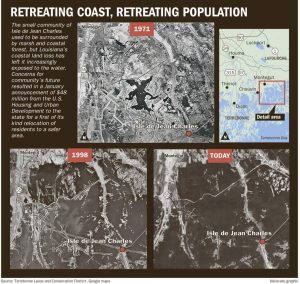

Even if member nations to the Paris Climate Agreement implement changes that effectively cut greenhouse gas emissions in the coming years, the impact on planetary temperatures and sea level rise won’t come in time to save the tiny town of Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana, which is already in the process of relocating its residents because it is quickly disappearing into the waters of

Even if member nations to the Paris Climate Agreement implement changes that effectively cut greenhouse gas emissions in the coming years, the impact on planetary temperatures and sea level rise won’t come in time to save the tiny town of Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana, which is already in the process of relocating its residents because it is quickly disappearing into the waters of  the Gulf of Mexico. Having lost 98 percent of its land since 1955, its 99 remaining residents have been labeled “America’s first climate refugees.”

the Gulf of Mexico. Having lost 98 percent of its land since 1955, its 99 remaining residents have been labeled “America’s first climate refugees.”

The remaining residents houses have been raised to the top of 15-foot stilts to evade increasingly omnipresent tidewaters. But the island is only connected to the mainland by a narrow two-lane road.  Years ago, it was buffered by marshlands. But those have all but disappeared and the seawater now laps at the road’s edges even on clear, calm days. But when the wind comes up and during heavy rainfall, the road is submerged under feet of seawater, cutting off residents from essential services such as fire and ambulance service and access to hospital and medical care.

Years ago, it was buffered by marshlands. But those have all but disappeared and the seawater now laps at the road’s edges even on clear, calm days. But when the wind comes up and during heavy rainfall, the road is submerged under feet of seawater, cutting off residents from essential services such as fire and ambulance service and access to hospital and medical care.

“The residents of Isle de Jean Charles won’t be alone in their exodus,” writes Michael Isaac Stein in an article posted by CityLab on January 24, 2018. “There will be up to 13 million climate refugees in the United States by the end of this century. Even if humanity were to stop all carbon emissions today, at least 414 towns, villages, and cities across the country would face relocation, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the

“The residents of Isle de Jean Charles won’t be alone in their exodus,” writes Michael Isaac Stein in an article posted by CityLab on January 24, 2018. “There will be up to 13 million climate refugees in the United States by the end of this century. Even if humanity were to stop all carbon emissions today, at least 414 towns, villages, and cities across the country would face relocation, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the  National Academy of Sciences. If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapses, researchers predict that the number will exceed 1,000.”

National Academy of Sciences. If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapses, researchers predict that the number will exceed 1,000.”

Stein goes on to report that “at least 17 communities, most of which are Native American or Native Alaskan, are already in the process of climate-related relocations. Yet despite its inevitability,  there is no official framework to handle this displacement. There is no U.S. government agency, process, or funding dedicated to confronting this impending humanitarian crisis.”

there is no official framework to handle this displacement. There is no U.S. government agency, process, or funding dedicated to confronting this impending humanitarian crisis.”

Isle de Jean Charles did receive a $48 million grant in 2016 to  relocate its own population. According to an article in the New York Times, the grant represents the first allocation of tax dollars to move an entire community because of the impact of climate change. “The divisions the effort has exposed and the logistical and moral dilemmas it has presented point up in microcosm the massive problems the world could face in the coming decades as it confronts a new category of displaced people

relocate its own population. According to an article in the New York Times, the grant represents the first allocation of tax dollars to move an entire community because of the impact of climate change. “The divisions the effort has exposed and the logistical and moral dilemmas it has presented point up in microcosm the massive problems the world could face in the coming decades as it confronts a new category of displaced people  who have become known as climate refuges,” writes New York Times correspondents Coral Davenport and Campbell Robertson in the article. “Around the globe, governments are confronting the reality that as human-caused climate change warms the planet, rising sea levels, stronger storms, increased flooding, harsher droughts and dwindling freshwater supplies

who have become known as climate refuges,” writes New York Times correspondents Coral Davenport and Campbell Robertson in the article. “Around the globe, governments are confronting the reality that as human-caused climate change warms the planet, rising sea levels, stronger storms, increased flooding, harsher droughts and dwindling freshwater supplies  could drive the world’s most vulnerable people from their homes.”

could drive the world’s most vulnerable people from their homes.”

According to the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security and the International Organization for Migration, between 50 and 200 million people could join Isle de Jean Charles and Pacific Islanders as climate refugees by 2050. Most of these are subsistence level farmers and fishermen.

For over a century, the American Indians living on Isle de Jean Charles fished, hunted, trapped and farmed among the lush banana and pecan trees that once spread out for acres. But, channels cut by loggers and oil companies eroded much of the island, and hurricanes such as Katrina, Rita, Gustav and, most recently, Harvey, have also taken a heavy toll. “What little remains will eventually be inundated as

For over a century, the American Indians living on Isle de Jean Charles fished, hunted, trapped and farmed among the lush banana and pecan trees that once spread out for acres. But, channels cut by loggers and oil companies eroded much of the island, and hurricanes such as Katrina, Rita, Gustav and, most recently, Harvey, have also taken a heavy toll. “What little remains will eventually be inundated as  burning fossil fuels melt polar ice sheets and drive up sea levels, projected the National Climate Assessment, a report of 13 federal agencies that highlighted the Isle de Jean Charles and its tribal residents as among the nation’s most vulnerable,” state Davenport and Robertson in their New York Times article.

burning fossil fuels melt polar ice sheets and drive up sea levels, projected the National Climate Assessment, a report of 13 federal agencies that highlighted the Isle de Jean Charles and its tribal residents as among the nation’s most vulnerable,” state Davenport and Robertson in their New York Times article.

Not surprisingly, the few people still living on the island are reluctant to leave. There’s a matter of heritage. They grew up there. Their parents and grandparents grew up there. Scores of family members lie at rest in the town’s cemetery. Moreover, there’s the fear of the unknown. Where to they go, how will the be received and what will they do for work and

Not surprisingly, the few people still living on the island are reluctant to leave. There’s a matter of heritage. They grew up there. Their parents and grandparents grew up there. Scores of family members lie at rest in the town’s cemetery. Moreover, there’s the fear of the unknown. Where to they go, how will the be received and what will they do for work and  school when they get there?

school when they get there?

“This is not just a simple matter of writing a check and moving happily to a place where they are embraced by their new neighbors,” notes Mark Davis, the director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy. “If you have a hard time moving dozens of people,” he continued, “it becomes impossible in any kind of organized or fair way to  move thousands, or hundreds of thousands, or, if you look at the forecast for South Florida, maybe even millions.”

move thousands, or hundreds of thousands, or, if you look at the forecast for South Florida, maybe even millions.”

Thus, Isle de Jean Charles is being looked at as kind of a “test run of sorts, a first-of-its-kind program that aims to create guiding principles for future resettlements,” notes Stein in his CityLab article,  “How to Save a Town from Rising Waters.”

“How to Save a Town from Rising Waters.”

What makes the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement project unique is that instead of buying out individual residents and leaving them to their own devices to restart their lives someplace else, the goal here is to resettle the entire community together, as a whole, by constructing a brand new town and filling it with the displaced occupants and culture of Isle de Jean Charles.

As nice as this sounds, the concept is fraught with practical, administrative difficulties. “Nearly  two years after the project began, nothing’s been built. There is still no blueprint for the new town; the project’s administrators are just now narrowing down possible locations and entering contract negotiations with the engineering and architectural firm, CSRS, they hope will design it.”

two years after the project began, nothing’s been built. There is still no blueprint for the new town; the project’s administrators are just now narrowing down possible locations and entering contract negotiations with the engineering and architectural firm, CSRS, they hope will design it.”

But the remaining residents of Isle de Jean Charles don’t have the luxury of this kind of time.

Nor will other climate refugees in the future.

Nor will other climate refugees in the future.

For most towns and cities, the best practice will be to retro-fit buildings and infrastructure to prevent or limit flooding.

But there are towns for whom it’s already too late. “There will need to be a proper government apparatus to deal with this,” concludes Steiin in his CityLab article.  “And those involved in the Isle de Jean Charles relocation believe that the lessons they learn will be invaluable for a future administration that takes the threat of climate displacement seriously.”

“And those involved in the Isle de Jean Charles relocation believe that the lessons they learn will be invaluable for a future administration that takes the threat of climate displacement seriously.”

Michael Stein is a freelance writer and photographer who is based in New Orleans.

January 26, 2018.

January 26, 2018.

RELATED POSTS.

- ‘Before the Flood’ delivers sobering climate change message to BIFF audience

- Sea level rise could inundate 1.9 million U.S. homes

- Rising sea levels could threaten Statue of Liberty and other historic sites

Sea level rise already a reality in portions of Alaska

Sea level rise already a reality in portions of Alaska- Vince Giordano and The Nighthawks documentary to open Bonita International Film Festival

- Cineastes to don flapper dresses and dancing shoes for BIFF opening night red carpet gala

BIFF opening night after-party perfect venue for practicing East and West Coast Swing

BIFF opening night after-party perfect venue for practicing East and West Coast Swing- Vince Giordano documentary furthers BIFF tradition of focusing on dance at festival opening

- A dance party broke out at the BIFF opening night VIP after-party

BIFF includes two Elizabeth D’Onofrio workshops on Saturday

BIFF includes two Elizabeth D’Onofrio workshops on Saturday- ‘Piper’ an achievement in photo-realist animated storytelling

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.