‘Cuba Reframed’ offers many discoveries about Cuba’s history and people

In 1984, Captiva’s favorite son launched the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange. ROCI was an egalitarian initiative intended to foster communication with other nations by creating a forum in the countries he visited where artists, sculptors, poets and authors from around the globe could meet and exchange creative ideas in a spirit of collaboration.

In 1984, Captiva’s favorite son launched the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange. ROCI was an egalitarian initiative intended to foster communication with other nations by creating a forum in the countries he visited where artists, sculptors, poets and authors from around the globe could meet and exchange creative ideas in a spirit of collaboration.  Cuba was the fourth country on Rauschenberg’s short list. And Cuba was similarly the destination of a recent expedition of artists, filmmakers, marine biologists, and several free spirits that departed Key West on board the Conch Republic flagship, The Wolf, just before the Trump Administration re-imposed

Cuba was the fourth country on Rauschenberg’s short list. And Cuba was similarly the destination of a recent expedition of artists, filmmakers, marine biologists, and several free spirits that departed Key West on board the Conch Republic flagship, The Wolf, just before the Trump Administration re-imposed the travel embargo on the island nation. This unique journey was filmed by John Biffar and presented in his compelling documentary Cuba Reframed.

the travel embargo on the island nation. This unique journey was filmed by John Biffar and presented in his compelling documentary Cuba Reframed.

Through ROCI, Rauschenberg gave the people in the countries he  visited the rare privilege of seeing themselves through his eyes and keen intellect. While The Wolf’s passengers certainly served as ambassadors and emissaries to the Cuban people, the thrust of the “Waves of Change Peace Vision” voyage was

visited the rare privilege of seeing themselves through his eyes and keen intellect. While The Wolf’s passengers certainly served as ambassadors and emissaries to the Cuban people, the thrust of the “Waves of Change Peace Vision” voyage was  more about piercing the aura of intrigue and mystery that enshrouds the island that sits a mere 90 miles from the Florida Keys.

more about piercing the aura of intrigue and mystery that enshrouds the island that sits a mere 90 miles from the Florida Keys.

“The Cubans know a lot more about us than we know about them,” Biffar notes. “They have access to CNN and they see our TV. But we really don’t know what goes on there.”

While no single documentary can shed light on Cuba’s majestic landscape and vibrant, flourishing culture, Cuba Reframed does provide insight into and share the perspective of the people who inhabit the eighth largest island nation in the world today.

The joie de vivre of the Cuban people

“[The film] expresses the spirit of the Cuban people,” remarks Rebecca Tobias of Waves of Change. “This trip was an incredible adventure for me both personally and professionally.”

“[The film] expresses the spirit of the Cuban people,” remarks Rebecca Tobias of Waves of Change. “This trip was an incredible adventure for me both personally and professionally.”

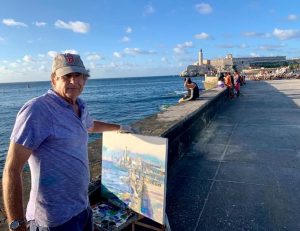

Biffar’s camera captures colorful classic cars motoring through the  streets of Havana, locals congregating and mixing companionably with tourists along the five-mile seawall known as the Malecon that lines Havana Harbor, and the street music that expresses the life rhythm of the Cuban people. His cinematography provides breathtaking views of pristine sandy beaches, bucolic agrarian panoramas and unexpected mountainous terrain. And, yes, it betrays the decaying buildings and gnawing poverty of an agriculture-based economy seemingly stuck in time. But Cuba Reframed is not an

streets of Havana, locals congregating and mixing companionably with tourists along the five-mile seawall known as the Malecon that lines Havana Harbor, and the street music that expresses the life rhythm of the Cuban people. His cinematography provides breathtaking views of pristine sandy beaches, bucolic agrarian panoramas and unexpected mountainous terrain. And, yes, it betrays the decaying buildings and gnawing poverty of an agriculture-based economy seemingly stuck in time. But Cuba Reframed is not an  unapologetic travelogue. Biffar’s documentary pushes beyond the façade of bustling tourism, shimmering shores and Spanish architecture to reveal a people characterized by generosity, kindness and affection who revel in life’s simple

unapologetic travelogue. Biffar’s documentary pushes beyond the façade of bustling tourism, shimmering shores and Spanish architecture to reveal a people characterized by generosity, kindness and affection who revel in life’s simple  pleasures.

pleasures.

This latter observation is perhaps the biggest surprise for the film’s American viewers, who typically attach great importance to the trappings of success, such as the homes in which they live, the cars they drive, the phones they employ to run their lives and the toys they accumulate. By contrast, the vast majority of the Cuban people depicted in the documentary  live in comparative poverty, yet they seem happier, more ebullient and contented than their U.S. counterparts.

live in comparative poverty, yet they seem happier, more ebullient and contented than their U.S. counterparts.

The film encapsulates this reality through a memorable sound bite: “The best part of capitalism is the lifestyle and the worst part is the society. Conversely, the worst part of communism is the economy and the best part is society.”

Whether  it’s the difference in economic system or the exigencies foist upon them by 70 years of U.S. embargo, the fact is that Cuban people place far more importance on family, fun and their day-to-day life experiences than on acquiring the latest styles, technology and other possessions.

it’s the difference in economic system or the exigencies foist upon them by 70 years of U.S. embargo, the fact is that Cuban people place far more importance on family, fun and their day-to-day life experiences than on acquiring the latest styles, technology and other possessions.

“They’re such beautiful people, welcoming and loving,” Biffar sum up. Like Aristides Paris, an amazingly accommodating tour guide featured in the film.

Coral reefs and environmental strides

American viewers are also likely to be surprised by the remarkable health of the beautiful reefs that line Cuba’s shores. Most attribute this to the absence of American tourists as a result of the economic embargo imposed in 1961.

American viewers are also likely to be surprised by the remarkable health of the beautiful reefs that line Cuba’s shores. Most attribute this to the absence of American tourists as a result of the economic embargo imposed in 1961.

Before Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, an enormous percentage of the Cuban economy was under the control of U.S. corporations, which controlled a significant percentage of the island’s natural resources (oil, minerals and timber), as well as its sugar, cattle, tobacco, timber, and farming industries. U.S. companies even dominated the island’s utilities and railroads. Castro’s communist government nationalized all of these assets, claiming them in the name of the Cuban people and the U.S. retaliated by slapping a trade embargo in place in hopes of toppling the Cuban government. The embargo didn’t have that effect, but it did

island’s natural resources (oil, minerals and timber), as well as its sugar, cattle, tobacco, timber, and farming industries. U.S. companies even dominated the island’s utilities and railroads. Castro’s communist government nationalized all of these assets, claiming them in the name of the Cuban people and the U.S. retaliated by slapping a trade embargo in place in hopes of toppling the Cuban government. The embargo didn’t have that effect, but it did  remove all incentive to develop the coastline, especially along its southern shore.

remove all incentive to develop the coastline, especially along its southern shore.

“[C]oastal development and overfishing … [are] what’s killing reefs,” observes David Guggenheim, founder and president of Ocean Doctor, a DC-based non-profit that’s dedicated to ocean conservation efforts in Cuba and elsewhere. “Sedimentation and nutrient pollution fuel the growth of algae, which then smothers the coral.”

Corals all over the world are dying by the acre. The demise of these animals and the delicate reefs they construct is one of the most dire and definitive indicators of ocean environmental damage on a global scale.

Coral extinction  spells doom for ocean systems — and, possibly, for the planet.

spells doom for ocean systems — and, possibly, for the planet.

“The problem is we’re not only fertilizing the oceans with sewage and agricultural runoff,” Guggenheim explains. “We’re also taking out of the ocean the fish that eat the algae and keep the reefs clean.”

Over the past 50 years, half of the Caribbean’s coral reefs have died. But during that span, the Biffar documentary reveals, Cuba took bold action to create extensive coral reef preserves. The preserves provide safe havens for fish, enabling them to increase their populations.

And to protect the preserves,  Cuba has curbed development along its adjoining shores. Today, its reefs are some of the healthiest and most bountiful in the world.

Cuba has curbed development along its adjoining shores. Today, its reefs are some of the healthiest and most bountiful in the world.

“By stemming U.S. tourism, the embargo has limited the amount of coastal development in Cuba that would have been needed to accommodate those millions of Americans,” adds Guggenheim.  “Also, it limited local fishing, recreational and otherwise,” allowing the reefs to thrive.

“Also, it limited local fishing, recreational and otherwise,” allowing the reefs to thrive.

The film underscores that we can learn much from Cuba’s efforts to preserve and protect its coral reefs.

Embracing Ernest Hemingway

Another discovery that’s likely to astonish American viewers is how the Cuban people have taken possession of Ernest Hemingway (A Moveable Feast, For Whom the Bell Tolls, A Farewell to Arms, Islands in the Stream).

Another discovery that’s likely to astonish American viewers is how the Cuban people have taken possession of Ernest Hemingway (A Moveable Feast, For Whom the Bell Tolls, A Farewell to Arms, Islands in the Stream).

Hemingway was a global citizen. He grew up in the suburbs outside of Chicago, fished and played baseball in Michigan, wrote  and hunted in Idaho, witnessed bullfights and civil war in Spain and became a charter member of the Lost Generation as he mingled with Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald and others in France. But it was Cuba that captured Hemingway’s mind, heart and soul. It was in the fishing village of Cojimar, east of Havana, that he built the villa he named Finca Vigía or Lookout Farm. And it was from Finca Vigia that he fished the local waters from his boat the

and hunted in Idaho, witnessed bullfights and civil war in Spain and became a charter member of the Lost Generation as he mingled with Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald and others in France. But it was Cuba that captured Hemingway’s mind, heart and soul. It was in the fishing village of Cojimar, east of Havana, that he built the villa he named Finca Vigía or Lookout Farm. And it was from Finca Vigia that he fished the local waters from his boat the Pilar, puffed Cuban cigars, frequented the local watering holes and eateries and wrote his masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea, which garnered both a Pulitzer and Noble Literary Prize. And Hemingway scholar and biographer Andrew Feldman was one of the twelve who made the voyage aboard the schooner Wolf from Key West to

Pilar, puffed Cuban cigars, frequented the local watering holes and eateries and wrote his masterpiece, The Old Man and the Sea, which garnered both a Pulitzer and Noble Literary Prize. And Hemingway scholar and biographer Andrew Feldman was one of the twelve who made the voyage aboard the schooner Wolf from Key West to  Havana.

Havana.

At the time of the voyage, Feldman was still basking in the afterglow of the publication of Ernesto, the definitive look at a definitive part of Hemingway’s life, and Cuba Reframed plumbs some of the discoveries Feldman shares in his meticulously-researched life-and-times tome about an extraordinary life  lived during extraordinary times.

lived during extraordinary times.

For example, through the film we learn that Hemingway actually came to think of himself as more Cuban than American. While he visited the island periodically between 1928 and 1938, he made Cuba his home beginning in 1939. Over the course of the next 21 years,  he didn’t just befriend the locals. He lived with and among them and they inspired the novel that rescued his flagging career, The Old Man and the Sea. And did it ever! It garnered him first a Pulitzer and a year later the Nobel Prize in Literature, and in a rare gesture of humility, Hemingway announced to the press that he accepted the coveted Nobel “as a citizen of Cojímar.”

he didn’t just befriend the locals. He lived with and among them and they inspired the novel that rescued his flagging career, The Old Man and the Sea. And did it ever! It garnered him first a Pulitzer and a year later the Nobel Prize in Literature, and in a rare gesture of humility, Hemingway announced to the press that he accepted the coveted Nobel “as a citizen of Cojímar.”

Interestingly, it wasn’t the Cuban dictator that asked Hemingway to leave Cuba after he ascended to power in 1959. (The two met only once, at a fishing tournament that Hemingway sponsored and which, ironically, Castro won even though it was his first time angling.) Rather it was U.S. Ambassador Philip Bonsall who told Hemingway that he needed to give up his beloved tropical home as an “act of patriotism.” Hemingway fiercely refused, and the documentary hints at the possibility that Hemingway’s ensuing

Interestingly, it wasn’t the Cuban dictator that asked Hemingway to leave Cuba after he ascended to power in 1959. (The two met only once, at a fishing tournament that Hemingway sponsored and which, ironically, Castro won even though it was his first time angling.) Rather it was U.S. Ambassador Philip Bonsall who told Hemingway that he needed to give up his beloved tropical home as an “act of patriotism.” Hemingway fiercely refused, and the documentary hints at the possibility that Hemingway’s ensuing  death in Idaho later that year may not have been suicide at all.

death in Idaho later that year may not have been suicide at all.

As fun and satisfying the black-and-white trip back in time is, what comes shining through Ernesto and Cuba Reframed is how beloved Hemingway is in present-day Cuba. In a sense, the Cuban people have appropriated the iconic American author, making him their very own. And today, Finca Vigia is one of the most popular tourist destinations in all of Cuba, compliments of a $1 million restoration project.

Biffar’s latest  documentary unquestionably provides a window into the history and people of Cuba in a way that’s fresh and new. In the same way that Rauschenberg used ROCI to give the countries he visited the privilege of seeing themselves through his discerning eye and keen intellection, Biffar employs his own special brand of docu-storytelling to introduce new generations of Americans to the people and culture of an island that’s been closed to them for more than 50 years.

documentary unquestionably provides a window into the history and people of Cuba in a way that’s fresh and new. In the same way that Rauschenberg used ROCI to give the countries he visited the privilege of seeing themselves through his discerning eye and keen intellection, Biffar employs his own special brand of docu-storytelling to introduce new generations of Americans to the people and culture of an island that’s been closed to them for more than 50 years.

“It’s time we  unite any way we can,” says Biffar. “Not focus on our differences, but focus on what we have in common, and the planet is what we have in common and we can learn a lot from the Cubans in that respect.”

unite any way we can,” says Biffar. “Not focus on our differences, but focus on what we have in common, and the planet is what we have in common and we can learn a lot from the Cubans in that respect.”

Cuba Reframed was unquestionably one of the many highlights of this year’s Fort Myers Film Festival. And the documentary underscores yet another important lesson. You miss the festival – and TGIM – at your own risk. You never know what “discoveries” Eric Raddatz has in store for your viewing pleasure!

October 29, 2020.

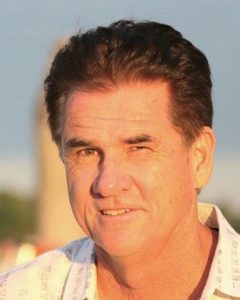

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.