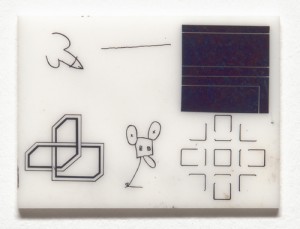

Rauschenberg’s ‘Page 21, Paragraph 3’ transfer solvent print

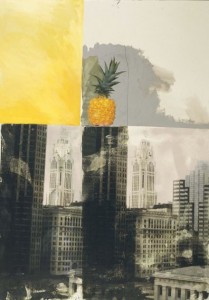

Late in his career, Robert Rauschenberg created a series of 7-by-5-foot paintings utilizing a process by which he transferred photographic images in pigment and vegetable dye onto a poly-laminate surface. He called the series Short Stories, and each painting in the 2001 set was arranged in a pre-determined sequence to create a visual story. The paintings’ titles make reference to random page and paragraph numbers—for example, Page 11, Paragraph 8 or Page 21, Paragraph 3. — as if it were part of a larger story.

Late in his career, Robert Rauschenberg created a series of 7-by-5-foot paintings utilizing a process by which he transferred photographic images in pigment and vegetable dye onto a poly-laminate surface. He called the series Short Stories, and each painting in the 2001 set was arranged in a pre-determined sequence to create a visual story. The paintings’ titles make reference to random page and paragraph numbers—for example, Page 11, Paragraph 8 or Page 21, Paragraph 3. — as if it were part of a larger story.

“The resultant effect is such that, upon encountering and ‘reading’ the composite work, the viewer feels as though he has been dropped  into the middle of an unknown story,” states the press release issued by New York’s Pace Gallery for their April 4-May 3, 2003 exhibition of Robert Rauschenberg Short Stories by You Are the Author.

into the middle of an unknown story,” states the press release issued by New York’s Pace Gallery for their April 4-May 3, 2003 exhibition of Robert Rauschenberg Short Stories by You Are the Author.

Robert Rauschenberg amplified his intent in the statement he wrote to accompany the exhibition. “It can only be art, linger and wonder wherever your mind takes you,” he wrote. “In this group of works there are no mistakes nor right, nor wrong. They are acronical of what you personally see or imagine. No tracks. No traces. Your story or dream and imagined or real these are your personal treasures to share or keep secret, choose to expand your reality or live it in the future…”

The print has not actually been donated yet. It gift is promised to FGCU by an anonymous donor.

Why Page 21, Paragraph 3 is significant

Page 21, Paragraph 3 is significant in the context of Robert Rauschenberg’s overall body of work because it is one of his solvent transfer prints. Though it is debatable whether Bob was the first artist to create prints in this way, his transfers of newspaper articles and photographs to canvas broke the mold in mixed-media printmaking. The ability to transfer current events into fine art by lifting text and photographic images from newspapers and magazines enabled him to pioneer a revolutionary path from abstract expressionism to Pop Art.

Page 21, Paragraph 3 is significant in the context of Robert Rauschenberg’s overall body of work because it is one of his solvent transfer prints. Though it is debatable whether Bob was the first artist to create prints in this way, his transfers of newspaper articles and photographs to canvas broke the mold in mixed-media printmaking. The ability to transfer current events into fine art by lifting text and photographic images from newspapers and magazines enabled him to pioneer a revolutionary path from abstract expressionism to Pop Art.

He is said to have discovered the process by accident in 1958. As the story goes, some solvent got spilled on some newspapers that were laying on a canvas. When he picked up the papers, he noticed that the newsprint and photographs had transferred onto the surface of the canvas. To anyone else, that would have been a nuisance. For Rauschenberg, it was an “aha” moment that he discerned could be the advent of an entirely new

He is said to have discovered the process by accident in 1958. As the story goes, some solvent got spilled on some newspapers that were laying on a canvas. When he picked up the papers, he noticed that the newsprint and photographs had transferred onto the surface of the canvas. To anyone else, that would have been a nuisance. For Rauschenberg, it was an “aha” moment that he discerned could be the advent of an entirely new  way to create art. With that, the discipline of transfer printmaking was borne and it has since inspired generations of printmakers to find new ways to cause images to transfer to other supports and surfaces.

way to create art. With that, the discipline of transfer printmaking was borne and it has since inspired generations of printmakers to find new ways to cause images to transfer to other supports and surfaces.

Though it all started with newspaper clippings, the most common forms of transfer printmaking today involve photocopies or laser printer printouts. These toner-based techniques seem to give the best results. The reason for this lies in the nature of the toner, itself. Toner is comprised mostly of carbon and polymers or waxes that are sensitive to electrostatic charges. Through a complex process, these charged particles are attracted and then fused to the paper under heat and pressure. Different transfer techniques use varying approaches to undo this binding done by the polymers or waxes and create a new bond for the carbon (pigment) particles.

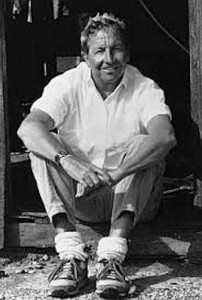

About Bob Rauschenberg

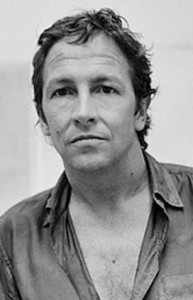

Robert Rauschenberg was born in Port Arthur, Texas on October 22, 1925. After serving in the military during World War II, he began studying art in 1947 at the Kansas City Art Institute. After that, he attended Academie Julien in Paris. He returned to the United States in 1948 to study under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, where he met avant-garde and creative partners John Cage and Merce Cunningham, with whom he would later collaborate.

Robert Rauschenberg was born in Port Arthur, Texas on October 22, 1925. After serving in the military during World War II, he began studying art in 1947 at the Kansas City Art Institute. After that, he attended Academie Julien in Paris. He returned to the United States in 1948 to study under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, where he met avant-garde and creative partners John Cage and Merce Cunningham, with whom he would later collaborate.

While taking classes at the Art Students League in New York from 1949 to 1951, Rauschenberg was offered his first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery. Some works from this period include blueprints, monochromatic white paintings, and black paintings.

From Fall 1952 to Spring 1953, he traveled to Europe and North Africa with Cy Twombly, whom he had met at the Art Students League. During his travels, Rauschenberg worked on a series of small collages, hanging assemblages, and small boxes filled with found elements, which he exhibited in Rome and Florence.

From Fall 1952 to Spring 1953, he traveled to Europe and North Africa with Cy Twombly, whom he had met at the Art Students League. During his travels, Rauschenberg worked on a series of small collages, hanging assemblages, and small boxes filled with found elements, which he exhibited in Rome and Florence.

After returning to the United States in 1953, Rauschenberg established a studio on Fulton Street in Manhattan. Jasper Johns occupied a neighboring studio and the two of them exchanged ideas, discussed work and collaborated with Black Mountain alums John Cage and Merce Cunningham, contributing scenic, costume, and lighting design to the latter’s dance company.

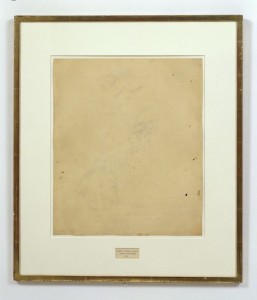

One of Rauschenberg and Johns’ first projects created quite a stir in the art world. Rauschenberg obtained a drawing from Willem de Kooning, which he promptly erased, matted and placed in a gilded frame. Johns added the plate which identified the piece. Most art critics and professionals accused Rauschenberg of being disrespectful. Bob countered that to the contrary, he was paying homage to the iconic artist. Regardless of the school to which one subscribes, it was Rauschenberg’s stated objective with Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) to test the definition and limits of art. “These works recall and effectively extend

One of Rauschenberg and Johns’ first projects created quite a stir in the art world. Rauschenberg obtained a drawing from Willem de Kooning, which he promptly erased, matted and placed in a gilded frame. Johns added the plate which identified the piece. Most art critics and professionals accused Rauschenberg of being disrespectful. Bob countered that to the contrary, he was paying homage to the iconic artist. Regardless of the school to which one subscribes, it was Rauschenberg’s stated objective with Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) to test the definition and limits of art. “These works recall and effectively extend  the notion of the artist as creator of ideas, a concept first broached by Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) with his iconic readymades of the early twentieth century,” expounds the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which holds the erased de Kooning in its permanent collection. “With Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), Rauschenberg set out to discover whether an artwork could be produced

the notion of the artist as creator of ideas, a concept first broached by Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) with his iconic readymades of the early twentieth century,” expounds the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which holds the erased de Kooning in its permanent collection. “With Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), Rauschenberg set out to discover whether an artwork could be produced  entirely through erasure—an act focused on the removal of marks rather than their accumulation.”

entirely through erasure—an act focused on the removal of marks rather than their accumulation.”

Rauschenberg is credited with fostering many new disciplines and genres, and Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) is an early example of both performance and conceptual art. (Included with Rauschenberg in the vanguard of groundbreaking conceptual artists was Yoko Ono, whose work in this genre was presented by the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Florida SouthWestern State College in  Yoko Ono Imagine Peace, which was displayed in the Lee campus gallery between January 4 and March 29, 2014.)

Yoko Ono Imagine Peace, which was displayed in the Lee campus gallery between January 4 and March 29, 2014.)

In 1954, Rauschenberg produced his first ‘Combine’ works in which he brought together aspects of painting and sculpture, incorporating materials traditionally considered to be outside the artist’s reach.

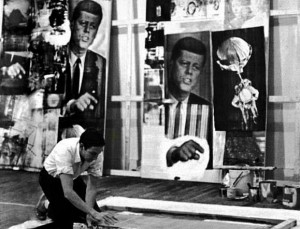

Ever the innovator, Rauschenberg turned his attention to silkscreening in 1962. By finding yet  another way to reference contemporary culture in his paintings and collages, he became a pivotal figure in the development of Pop Art.

another way to reference contemporary culture in his paintings and collages, he became a pivotal figure in the development of Pop Art.

Bob enjoyed his first retrospective, organized by the Jewish Museum, New York, in 1963 and was awarded the Grand Prize for painting at the 1964 Venice Biennale. He spent much of the remainder  of the 1960s dedicated to more collaborative projects, including printmaking, performance, choreography, set design, and art-and-technology works. In 1966, he cofounded Experiments in Art and Technology, an organization that sought to promote collaborations between artists and engineers.

of the 1960s dedicated to more collaborative projects, including printmaking, performance, choreography, set design, and art-and-technology works. In 1966, he cofounded Experiments in Art and Technology, an organization that sought to promote collaborations between artists and engineers.

Over the following decades, Rauschenberg’s work  continued to encompass a variety of fields. Toward the end of 1970, he made another decision that proved significant to those of us living in Southwest Florida. Tired of the art scene in New York, he established his permanent residence and studio in Captiva Island, Florida, where he acquired 20 acres of the island to use a workspace and serve as a nature preserve. His first project on Captiva was a 16.5-meter-long silkscreen print called Currents (1970), made with newspapers from the first two months of the year, followed by Cardboards (1970–71) and Early Egyptians (1973–74), the latter of which is a series of wall reliefs and sculptures constructed from many of the used boxes he’d packed his things in when he made the move from New York. He also

continued to encompass a variety of fields. Toward the end of 1970, he made another decision that proved significant to those of us living in Southwest Florida. Tired of the art scene in New York, he established his permanent residence and studio in Captiva Island, Florida, where he acquired 20 acres of the island to use a workspace and serve as a nature preserve. His first project on Captiva was a 16.5-meter-long silkscreen print called Currents (1970), made with newspapers from the first two months of the year, followed by Cardboards (1970–71) and Early Egyptians (1973–74), the latter of which is a series of wall reliefs and sculptures constructed from many of the used boxes he’d packed his things in when he made the move from New York. He also  printed on textiles using his solvent-transfer technique to make the Hoarfrosts (1974–76) and Spreads (1975–82), and for the Jammers (1975–76), he created a series of colorful silk wall and floor works.

printed on textiles using his solvent-transfer technique to make the Hoarfrosts (1974–76) and Spreads (1975–82), and for the Jammers (1975–76), he created a series of colorful silk wall and floor works.

A retrospective organized by the National Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum), Washington, D.C.,  traveled throughout the United States in 1976 and 1978. In between, Rauschenberg, Cunningham, and Cage reconnected as collaborators for the first time in 13 years when the Merce Cunningham Dance Company performed Travelogue (1977), for which Rauschenberg contributed the costume and set designs.

traveled throughout the United States in 1976 and 1978. In between, Rauschenberg, Cunningham, and Cage reconnected as collaborators for the first time in 13 years when the Merce Cunningham Dance Company performed Travelogue (1977), for which Rauschenberg contributed the costume and set designs.

After he settled a copyright lawsuit brought against him in 1980 for an earlier appropriation of an advertisement, Rauschenberg shifted to exclusively using his own photographs as material for  works that involved photography. His return to that medium led to exhibitions in Florida and Paris over the next two years, which, for the first time, featured his black-and-white photographs from the 1950s as well as his more current photographs taken in various cities around the United States. In 1981 he began work on The 1/4 Mile or Two Furlong Piece (1981–2008), conceived by the artist to be the longest artwork in the world (and

works that involved photography. His return to that medium led to exhibitions in Florida and Paris over the next two years, which, for the first time, featured his black-and-white photographs from the 1950s as well as his more current photographs taken in various cities around the United States. In 1981 he began work on The 1/4 Mile or Two Furlong Piece (1981–2008), conceived by the artist to be the longest artwork in the world (and  eventually extending beyond the length designated in the title). It encompassed a wide range of Rauschenberg’s techniques and a chronology of his imagery.

eventually extending beyond the length designated in the title). It encompassed a wide range of Rauschenberg’s techniques and a chronology of his imagery.

Rauschenberg traveled extensively throughout his life, but in the mid-1980s, his collaborations with artisans and workshops abroad culminated in the establishment of the Rauschenberg Overseas  Culture Interchange (ROCI). Announced to the United Nations in December 1984, ROCI involved the artist making and presenting work while traveling with a team of assistants through 11 politically sensitive countries, including China, Tibet, the U.S.S.R., East Germany and Cuba as a way to initiate cross-cultural dialogue.

Culture Interchange (ROCI). Announced to the United Nations in December 1984, ROCI involved the artist making and presenting work while traveling with a team of assistants through 11 politically sensitive countries, including China, Tibet, the U.S.S.R., East Germany and Cuba as a way to initiate cross-cultural dialogue.

Rauschenberg was all about collaboration long before he launched ROCI in 1984. “From his joint efforts in the late 1940’s with his former wife, Susan Weil, to multimedia performance art with Merce Cunningham and John Cage in the 1960’s, to suites of prints and sculptures in studios at Universal Limited Art Editions on Long Island, Gemeni G.E.L. in Los Angeles and GraficStudio in Tampa, Fla., he has always worked closely with

Rauschenberg was all about collaboration long before he launched ROCI in 1984. “From his joint efforts in the late 1940’s with his former wife, Susan Weil, to multimedia performance art with Merce Cunningham and John Cage in the 1960’s, to suites of prints and sculptures in studios at Universal Limited Art Editions on Long Island, Gemeni G.E.L. in Los Angeles and GraficStudio in Tampa, Fla., he has always worked closely with  others,” wrote art critic Roberta Smith in a 1991 review. “In his own working compound in Captiva, Fla., he is surrounded by young artist-assistants. Even his art ‘’collaborates.’’ He mixes media, objects and images, causing them to relate to each other in a new way.”

others,” wrote art critic Roberta Smith in a 1991 review. “In his own working compound in Captiva, Fla., he is surrounded by young artist-assistants. Even his art ‘’collaborates.’’ He mixes media, objects and images, causing them to relate to each other in a new way.”

“To communicate is the goal,” Bob once summarized, but his overarching aim was clearly  to replace people’s preconceptions and misconceptions about each other with a vision of common humanity – especially in such insular countries as China, Chile, Cuba, East Germany, Malaysia and Tibet.

to replace people’s preconceptions and misconceptions about each other with a vision of common humanity – especially in such insular countries as China, Chile, Cuba, East Germany, Malaysia and Tibet.

“He was trying to introduce the world to itself,” Don Saff observed. Saff would know. The distinguished USF Professor Emeritus not only served as ROCI’s artistic director and organized the 1991 ROCI exhibition at the National Gallery (which served as the Interchange’s only U.S. venue), Saff helped produce Rauschenberg’s mixed media editions for the ROCI project as the founder and director of GraphicStudio.

While some works that Bob and his traveling minstrels created during ROCI remained in their original sites as gifts, others traveled with the ROCI team to be shared with future participants. Rauschenberg personally funded the project, which concluded in 1991 with an exhibition of over 125 works at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

While some works that Bob and his traveling minstrels created during ROCI remained in their original sites as gifts, others traveled with the ROCI team to be shared with future participants. Rauschenberg personally funded the project, which concluded in 1991 with an exhibition of over 125 works at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

“Based on his introduction to painting and screenprinting on copper during ROCI Chile in 1985, Rauschenberg created multiple series, such as  Urban Bourbons (1988–95), that focused on different methods of transferring images onto a variety of reflective metals, such as steel and aluminum,” states the Guggenheim in their online biography of Rauschenberg. “In addition, throughout the 1990s, Rauschenberg continued to use new materials while still working with more rudimentary techniques, such as wet fresco, as in the series Arcadian Retreat (1996), and the

Urban Bourbons (1988–95), that focused on different methods of transferring images onto a variety of reflective metals, such as steel and aluminum,” states the Guggenheim in their online biography of Rauschenberg. “In addition, throughout the 1990s, Rauschenberg continued to use new materials while still working with more rudimentary techniques, such as wet fresco, as in the series Arcadian Retreat (1996), and the  transfer of images by hand, as in the Anagrams (1995–2000). As part of his engagement with the latest technology, he began making digital Iris prints and using biodegradable vegetable dyes in his transfer processes, underscoring his commitment to caring for the environment. During this time, he also designed costumes and sets for several major productions by the Trisha Brown Dance Company in New York.”

transfer of images by hand, as in the Anagrams (1995–2000). As part of his engagement with the latest technology, he began making digital Iris prints and using biodegradable vegetable dyes in his transfer processes, underscoring his commitment to caring for the environment. During this time, he also designed costumes and sets for several major productions by the Trisha Brown Dance Company in New York.”

Rauschenberg’s work has been exhibited extensively over the last 50 years. The last major retrospective of Rauschenberg’s work while he was still living was held between 1997 and 1999, shown at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum and Guggenheim Museum Soho,  New York touring to The Menil Collection, Contemporary Arts Museum and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Museum Ludwig, Cologne and the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao.

New York touring to The Menil Collection, Contemporary Arts Museum and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Museum Ludwig, Cologne and the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao.

In 1998, the Vatican commissioned (and later refused) a work by Rauschenberg based on the Apocalypse for Renzo Piano’s pilgrimage church in Foggia, Italy. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, hosted a survey of the artist’s Combines (1999), and the Guggenheim Foundation organized the memorial exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: Gluts for the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (2009), which traveled to the Museum Tinguely, Basel (2009–10); Guggenheim  Museum Bilbao (2010); and Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese, Italy (2010–11). Rauschenberg’s last stage set was for Cunningham’s Xover (crossover) (2007), based on his own painting Plank (2003).

Museum Bilbao (2010); and Villa e Collezione Panza, Varese, Italy (2010–11). Rauschenberg’s last stage set was for Cunningham’s Xover (crossover) (2007), based on his own painting Plank (2003).

Despite a stroke in 2002 that paralyzed his right side, Rauschenberg continued to produce work in his Captiva Island studio with the assistance of his gallery assistants and staff, which included solvent transfer printmaker Darryl Pottorf and sculptor Lawrence Voytek. Rauschenberg died in Captiva on May 12, 2008.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.