The plight of Denmark’s Jews during World War II

Holocaust survivor Steen Metz will speak at The Laboratory Theater of Florida at 7:00 p.m. on Monday, April 2 as part of the Theater’s expanding tolerance and cultural education programming. His question and answer discussion coincides with Holocaust Remembrance Month in April.

Holocaust survivor Steen Metz will speak at The Laboratory Theater of Florida at 7:00 p.m. on Monday, April 2 as part of the Theater’s expanding tolerance and cultural education programming. His question and answer discussion coincides with Holocaust Remembrance Month in April.

Metz was born in  Odense, Denmark. He would have been just 5-years-old when German forces occupied Norway and Denmark in advance of their Blitzkrieg of Belgium, Holland and France a month later on May 10, 1940. Following the occupation, 1,700 Jews in Norway and 7,400 Jews in Denmark (1,400 of which were refugees from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia) were now within putative Nazi control. But at the insistence of Norwegian and Danish authorities, no harm came to the Jews living within their territorial borders.

Odense, Denmark. He would have been just 5-years-old when German forces occupied Norway and Denmark in advance of their Blitzkrieg of Belgium, Holland and France a month later on May 10, 1940. Following the occupation, 1,700 Jews in Norway and 7,400 Jews in Denmark (1,400 of which were refugees from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia) were now within putative Nazi control. But at the insistence of Norwegian and Danish authorities, no harm came to the Jews living within their territorial borders.

That changed  toward the end of September, 1942 when the Reich’s Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop ordered his attaches in Hungary, Bulgaria and Denmark to undertake negotiations with the provisional governments in those countries for the “evacuation of the Jews of these countries.”

toward the end of September, 1942 when the Reich’s Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop ordered his attaches in Hungary, Bulgaria and Denmark to undertake negotiations with the provisional governments in those countries for the “evacuation of the Jews of these countries.”

Steen Metz was now seven.

The negotiations went nowhere,  and the Germans finally lost patience. They declared martial law on August 28, 1943.

and the Germans finally lost patience. They declared martial law on August 28, 1943.

“The SS hoped to use the opportunity of martial law to deport all of Denmark’s Jews and half-Jews,” writes historian Martin Gilbert in The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War. “Forewarned of the planned  deportation, however, Danes and Jews plotted to ensure that, on the eve of deportation, Danish sea captains and fishermen ferried 5,919 Jews, 1,301 part-Jews – designated Jews by the Nazis – and 686 Christians married to Jews to neutral Sweden.”

deportation, however, Danes and Jews plotted to ensure that, on the eve of deportation, Danish sea captains and fishermen ferried 5,919 Jews, 1,301 part-Jews – designated Jews by the Nazis – and 686 Christians married to Jews to neutral Sweden.”

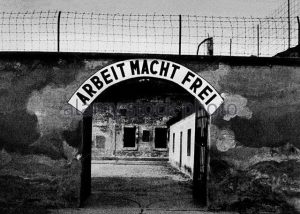

When the Germans showed up to begin the deportations on October 1, 1943, they found only 500 Jews  still remaining in Denmark. Regrettably, Steen Metz and his family were among that number, and all 500 were sent to Theresienstadt.

still remaining in Denmark. Regrettably, Steen Metz and his family were among that number, and all 500 were sent to Theresienstadt.

In late 1943 the King of Denmark, Christian X, demanded an inspection of Theresienstadt to determine the condition of Danish Jews sent there in October of that year. The review panel was to include two Swiss delegates from the International Red Cross and two representatives of the  Danish government. The Nazis permitted these representatives to visit the camp in order to dispel rumors about the extermination camps that were circulating in the world community.

Danish government. The Nazis permitted these representatives to visit the camp in order to dispel rumors about the extermination camps that were circulating in the world community.

The Germans immediately engaged in a beautification program, which they named “Operation Embellishment.” They built fake shops and cafés,  painted dormitory rooms, and reassigned the Danish Jews to apartments in which they had no more than three roommates. The improvements made it seem as though the Jews at Theresienstadt were living in relative comfort. But it was in reality little more than a ruse intended to mollify the king’s concerns.

painted dormitory rooms, and reassigned the Danish Jews to apartments in which they had no more than three roommates. The improvements made it seem as though the Jews at Theresienstadt were living in relative comfort. But it was in reality little more than a ruse intended to mollify the king’s concerns.

Weeks of  preparation preceded the visit, and as soon as the area was cleaned up, the Nazis deported many of Theresienstadt’s Jews to Auschwitz to minimize overcrowding. Most of the Czechoslovak workers assigned to “Operation Embellishment” were among those deported.

preparation preceded the visit, and as soon as the area was cleaned up, the Nazis deported many of Theresienstadt’s Jews to Auschwitz to minimize overcrowding. Most of the Czechoslovak workers assigned to “Operation Embellishment” were among those deported.

The inspection was held on June 23, 1944, with the four designated officials being hosted by Adolf Eichmann himself.  According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Red Cross issued “a bland report about the visit, indicating that the representatives were taken in by the elaborate fiction.”

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Red Cross issued “a bland report about the visit, indicating that the representatives were taken in by the elaborate fiction.”

Following the successful use of Terezin as a supposed model internment camp during the Red Cross visit, the Nazis decided to make a propaganda film there. It was directed by Jewish prisoner Kurt Gerron, an experienced director and actor. Shooting took eleven days, starting September 1, 1944. After the film was completed, most of the cast and the director were deported to Auschwitz. Gerron died in the gas

Following the successful use of Terezin as a supposed model internment camp during the Red Cross visit, the Nazis decided to make a propaganda film there. It was directed by Jewish prisoner Kurt Gerron, an experienced director and actor. Shooting took eleven days, starting September 1, 1944. After the film was completed, most of the cast and the director were deported to Auschwitz. Gerron died in the gas  chamber on October 28, 1944.

chamber on October 28, 1944.

Of the 500 Jews sent to Theresienstadt in 1943, 423 survived the war (as did all those who’d been ferried to Sweden – along with a further 3,000 Jewish refugees who’d  reached Sweden before the war from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia). A Swedish diplomat by the name of Count Folke Bernadotte negotiated their release on April 14, 1945.

reached Sweden before the war from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia). A Swedish diplomat by the name of Count Folke Bernadotte negotiated their release on April 14, 1945.

Steen Metz was 10 when he was liberated from Theresienstadt and safely returned to Denmark.

But he now faced an entirely new set of problems. Life for Holocaust survivors in post-war Europe  was still fraught with danger and immense challenges.

was still fraught with danger and immense challenges.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.