Subtle line speaks volumes about ‘Machinal’ director, actor and psychodrama itself

For the next two weekends, Machinal will be on stage in the FGCU TheatreLab. Written in 1927 and debuting a year later on Broadway, the play is eerily relevant today to women struggling under the yoke of a host of intractable #metoo, #time’s up, LGBTQ and gender inequality issues. Living in a patriarchal, male-dominated society is enough to drive a woman crazy. This is precisely what happens to the protagonist in Machinal, a young lady by the name of Helen.

For the next two weekends, Machinal will be on stage in the FGCU TheatreLab. Written in 1927 and debuting a year later on Broadway, the play is eerily relevant today to women struggling under the yoke of a host of intractable #metoo, #time’s up, LGBTQ and gender inequality issues. Living in a patriarchal, male-dominated society is enough to drive a woman crazy. This is precisely what happens to the protagonist in Machinal, a young lady by the name of Helen.

Playwright Sophie Treadwell doesn’t give us much backstory about  Helen’s early life or upbringing, but it’s clear that her mother has drummed societal expectations and strictures into her daughter with the iron fist of a drill sergeant. Apparently Helen has passed the age at which most girls marry and start families, and mom’s anxious to get her daughter married off, even if her daughter finds her suitor repugnant, sexually and otherwise.

Helen’s early life or upbringing, but it’s clear that her mother has drummed societal expectations and strictures into her daughter with the iron fist of a drill sergeant. Apparently Helen has passed the age at which most girls marry and start families, and mom’s anxious to get her daughter married off, even if her daughter finds her suitor repugnant, sexually and otherwise.

Helen is being pursued by her boss. He paws her during dictation.  Dictation takes place behind closed doors. Her co-workers know the boss’ dirty little secret. They talk openly among themselves about Helen and the workplace romance unfolding behind closed doors. Helen tries to talk to her mother about the situation. She’s hoping that mom will tell her to quit her job and find another. But all mom can see is that Helen’s not getting any younger and the boss has the ability to support not only Helen, but her too. She didn’t marry for love, so why should her daughter? Life’s about having a place to live, food on the table, and

Dictation takes place behind closed doors. Her co-workers know the boss’ dirty little secret. They talk openly among themselves about Helen and the workplace romance unfolding behind closed doors. Helen tries to talk to her mother about the situation. She’s hoping that mom will tell her to quit her job and find another. But all mom can see is that Helen’s not getting any younger and the boss has the ability to support not only Helen, but her too. She didn’t marry for love, so why should her daughter? Life’s about having a place to live, food on the table, and  clothes on your back.

clothes on your back.

Mom wants her to submit.

The boss wants her to submit.

Her co-workers expect her to give in as well.

It’s a theme repeated throughout the play. While women have more latitude 91 years later to marry for love or even go through life single, parents, employers and society at large still expect females to submit when it comes to a broad array of questions,  from abortion, gender identity and sexual orientation to socially-acceptable and legally-permissible responses to sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape (with one-third of the planet’s female population being subjected at least once during her lifetime to sexual assault and rape). And let’s not forget that this country has yet to elect a woman as president and women are grossly

from abortion, gender identity and sexual orientation to socially-acceptable and legally-permissible responses to sexual harassment, sexual assault and rape (with one-third of the planet’s female population being subjected at least once during her lifetime to sexual assault and rape). And let’s not forget that this country has yet to elect a woman as president and women are grossly  underrepresented in the film industry, television and the arts. Just ask the Guerrilla Girls if you’re not convinced.

underrepresented in the film industry, television and the arts. Just ask the Guerrilla Girls if you’re not convinced.

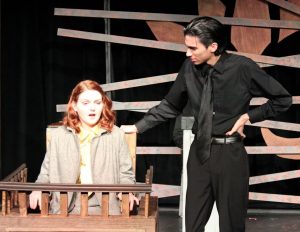

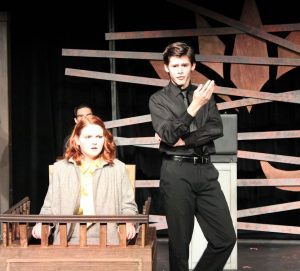

The play showcases Cassandra Dayton, a theater scholarship recipient who plays Helen with a high degree of insight and verve. Dayton does an exceptional job of portraying a woman who chafes at the prospect of having to live by everyone’s rules except her own, of being denied the right and power to make her own choices,  to give voice to the person who’d kill to be free of the stifling façade, veneer and muscular armor thrust upon her by unwelcome outside sources, including God and religion.

to give voice to the person who’d kill to be free of the stifling façade, veneer and muscular armor thrust upon her by unwelcome outside sources, including God and religion.

Helen ultimately offs her husband with a blow to the temple using a bottle filled with small stones given to her by an extramarital paramour. [It takes place off stage.] In  traditional theater, fiction and true crime writing, there’d be a rush to explain why the young lady resorted to murder at that time and place. In fact, Treadwell gives voice to this literary custom. “If you didn’t want to be married any longer, why didn’t you just divorce him,” the prosecutor demands. But then Treadwell does a 180. “I just couldn’t hurt him like that,” Helen answers honestly,

traditional theater, fiction and true crime writing, there’d be a rush to explain why the young lady resorted to murder at that time and place. In fact, Treadwell gives voice to this literary custom. “If you didn’t want to be married any longer, why didn’t you just divorce him,” the prosecutor demands. But then Treadwell does a 180. “I just couldn’t hurt him like that,” Helen answers honestly,  eliciting involuntary peals of laughter from the press corps and others sitting in the courtroom gallery.

eliciting involuntary peals of laughter from the press corps and others sitting in the courtroom gallery.

Dayton utters the line with incredible innocence, even sweetness. Remember, this is an Expressionist drama. The play doesn’t purport to reveal an iota about the sociology of a murderess. It doesn’t bother to advance a theory about what would cause this girl to progress from adultery to murder, especially since her illicit lover has moved on and is no longer  with her.

with her.

No, Machinal is told from Helen’s perspective, and from her interior framework, the swift act of killing was less painful and traumatic than the emotional upheaval and ordeal associated with separation, divorce and the necessity of figuring out how to provide for herself and her mother financially when all’s said and done.

It’s  a subtle thing, perhaps. A line delivered without fanfare or ostentation in the blink of an eye. Yet it says volumes about Cassandra Dayton’s talent and potential as an actor (both on stage and in film) and Dan Bacalzo’s level of expertise and insightfulness as a theater professor and director.

a subtle thing, perhaps. A line delivered without fanfare or ostentation in the blink of an eye. Yet it says volumes about Cassandra Dayton’s talent and potential as an actor (both on stage and in film) and Dan Bacalzo’s level of expertise and insightfulness as a theater professor and director.

There are many other areas in which this plays a part.

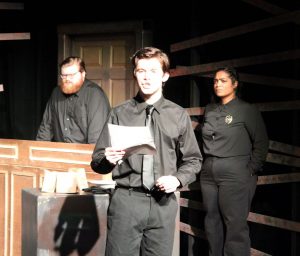

The freshman-heavy cast also includes Tyler Colmery as  Helen’s husband, Gabrielle Kadoo (Helen’s mother), Patrick Maikowski (lover), Joseph Herrera (adding clerk and defense laywer), Dane Futrell (filing clerk and prosecutor), Reid Ackerman (stenographer), Esther Zuercher (telephone girl) and Aimee Greco (nurse). All but Dayton plays various additional roles, as well.

Helen’s husband, Gabrielle Kadoo (Helen’s mother), Patrick Maikowski (lover), Joseph Herrera (adding clerk and defense laywer), Dane Futrell (filing clerk and prosecutor), Reid Ackerman (stenographer), Esther Zuercher (telephone girl) and Aimee Greco (nurse). All but Dayton plays various additional roles, as well.

Among the play’s many highlights is the courtroom scene during which Helen is questioned by both her criminal  defense attorney and the prosecutor. Both Joseph Herrera (defense) and Dane Futrell (prosecutor) are convincing as high-stakes litigators. Futrell, in particular, turns in a noteworthy performance. You’ll swear you’re watching a young Kevin Bacon stalking a witness in A Few Good Men.

defense attorney and the prosecutor. Both Joseph Herrera (defense) and Dane Futrell (prosecutor) are convincing as high-stakes litigators. Futrell, in particular, turns in a noteworthy performance. You’ll swear you’re watching a young Kevin Bacon stalking a witness in A Few Good Men.

The set is minimalist, even somewhat futuristic. So is the wardrobe.  Both are designed to keep the audience’s attention focused unwaveringly on the psychodrama unfolding on the TheatreLab floor. They also free the audience to transport this 1920s storyline to more modern application which, of course, is one reason Bacalzo chose this particular play.

Both are designed to keep the audience’s attention focused unwaveringly on the psychodrama unfolding on the TheatreLab floor. They also free the audience to transport this 1920s storyline to more modern application which, of course, is one reason Bacalzo chose this particular play.

You should plan on catching this play. Not only would the student actors appreciate your support, you’ll likely be seeing one or more on local stages in the years to come.

RELATED POSTS.

Ninety years later, ‘Machinal’ still resonates with female viewers

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.