‘Hand to God’ questions notion that people should strive to be good

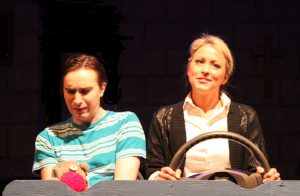

On stage at Laboratory Theater of Florida for the next two weekends is Robert Askins’ dark comedy Hand to God. The action, both physical and psychological, revolves around Margery and Jason, a mom and her teenage son who are desperately trying to come to terms with the death of their husband/father.

On stage at Laboratory Theater of Florida for the next two weekends is Robert Askins’ dark comedy Hand to God. The action, both physical and psychological, revolves around Margery and Jason, a mom and her teenage son who are desperately trying to come to terms with the death of their husband/father.

Death is hard to deal with under any circumstances. But here, it’s particularly tough because it comes with a heaping helping of abandonment.  Margery’s husband and Jason’s father, you see, literally ate himself to death. As a result, there’s no orderly progression for mother or son through the five stages of grief postulated by psychologist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross many years ago. In Hand to God, Margery and Jason are mired in anger, and both are acting out in self-destructive ways.

Margery’s husband and Jason’s father, you see, literally ate himself to death. As a result, there’s no orderly progression for mother or son through the five stages of grief postulated by psychologist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross many years ago. In Hand to God, Margery and Jason are mired in anger, and both are acting out in self-destructive ways.

Take Jason, for instance, played by Steven Coe. When we first meet him, it’s abundantly clear that he’s suffering from clinical depression. So when Margery  agrees to teach a puppetry class in the church basement to some of the town’s miscreant teens, she enrolls her son in the class in hopes of drawing the boy out of his hormone-amplified depressive shell. Fundamentalist Christian congregations often use puppets to teach youngsters how to follow the Bible and avoid Satan. In this case, the strategy backfires when Jason’s hand puppet becomes possessed by Satan himself.

agrees to teach a puppetry class in the church basement to some of the town’s miscreant teens, she enrolls her son in the class in hopes of drawing the boy out of his hormone-amplified depressive shell. Fundamentalist Christian congregations often use puppets to teach youngsters how to follow the Bible and avoid Satan. In this case, the strategy backfires when Jason’s hand puppet becomes possessed by Satan himself.

Sigmund Freud once theorized that depression is anger turned inward. But Jason’ hand puppet, Tyrone, provides the boy with  an outlet for his internalized wrath, redirecting it against everyone who crosses his path. There are plenty of deserving targets – from his mother and Timothy the Bully to God and his stand-in, Pastor Greg.

an outlet for his internalized wrath, redirecting it against everyone who crosses his path. There are plenty of deserving targets – from his mother and Timothy the Bully to God and his stand-in, Pastor Greg.

Jason has lots to be angry about. So much so, in fact, that it seems for a time that Jason-qua-Tyrone is actually inhabited by the devil himself. And as Coe’s remarkably rich tour de force performance unfolds across the stage, the audience and even Coe’s  cast mates find themselves wondering whether Askins’ tome has taken a nasty turn and is actually about demonic possession.

cast mates find themselves wondering whether Askins’ tome has taken a nasty turn and is actually about demonic possession.

Coe has developed by leaps and bounds since he first emerged on the stage in FSW’s Black Box Theatre, but he did not become a seasoned ventriloquist for Hand to God. You can see Coe’s lips move, assuming  you’re bothering to look at his face when Tyrone is talking. But by the time we get to the second scene of Act I (which takes place on a see-saw in the church playground), all eyes are focused squarely on Tyrone each time he speaks. Jason all but fades into the background, even as Tyrone berets him for his loyalty to his mother and inability to stand up for himself.

you’re bothering to look at his face when Tyrone is talking. But by the time we get to the second scene of Act I (which takes place on a see-saw in the church playground), all eyes are focused squarely on Tyrone each time he speaks. Jason all but fades into the background, even as Tyrone berets him for his loyalty to his mother and inability to stand up for himself.

The magic Coe  works through the character of Tyrone is spellbinding. In Coe’s hands (or to be more accurate, on Coe’s hand), the puppet takes on a life of his own. It’s not Jason who crosses the room at various junctures to confront his mother, Pastor Greg or Timothy. Rather, it’s Tyrone who hurtles through space, dragging a bewildered Jason and startled audience in his crazed Lyttan wake.

works through the character of Tyrone is spellbinding. In Coe’s hands (or to be more accurate, on Coe’s hand), the puppet takes on a life of his own. It’s not Jason who crosses the room at various junctures to confront his mother, Pastor Greg or Timothy. Rather, it’s Tyrone who hurtles through space, dragging a bewildered Jason and startled audience in his crazed Lyttan wake.

But while Tyrone provides much-needed agency for Jason’s rage and fury, Jason isn’t the puppet’s puppet. Organically,  the boy knows that he has to get rid of his anger in order to get better. In therapy, psychologists routinely give patients a whiffle ball bat for use on a pillow to underscore this point. Tyrone is too hard of a case for some puny hollow plastic bat. Something stronger, more substantial, is required for an exorcism of this caliber. You’ll see how that shakes loose during the penultimate scene in the church basement at the end of the play.

the boy knows that he has to get rid of his anger in order to get better. In therapy, psychologists routinely give patients a whiffle ball bat for use on a pillow to underscore this point. Tyrone is too hard of a case for some puny hollow plastic bat. Something stronger, more substantial, is required for an exorcism of this caliber. You’ll see how that shakes loose during the penultimate scene in the church basement at the end of the play.

There simply aren’t enough  superlatives to describe the work that Shelley Rae Sanders does in Hand to God. Where Coe is asked to explore and convey the myriad hues of rage and anger, the character of Margery requires Sanders to confront the loss of faith.

superlatives to describe the work that Shelley Rae Sanders does in Hand to God. Where Coe is asked to explore and convey the myriad hues of rage and anger, the character of Margery requires Sanders to confront the loss of faith.

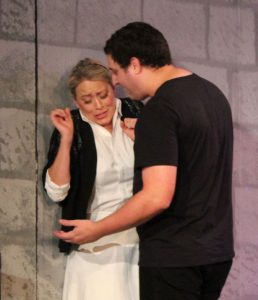

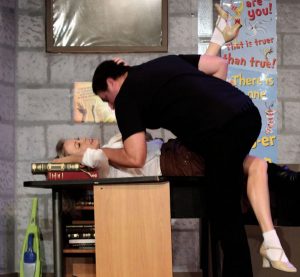

In Margery’s case, the loss of faith pertains to more than God and religion. Until her husband’s death, she operated on the premise that good things would happen to her and the people she loved provided she behaved as God and society ordained. But in Marjorie’s case, she’s  lost more than just faith in fairness. She’s lost faith in herself! Having defined herself and her self-worth in terms of wife, companion and mother, she’s adrift on the sea of life without paddle or rudder. Since the rules no longer apply, she’s suddenly free to engage in behaviors she would have once considered outrageous, scandalous and even blasphemous, including seducing an underage minor in the basement of the church she attends.

lost more than just faith in fairness. She’s lost faith in herself! Having defined herself and her self-worth in terms of wife, companion and mother, she’s adrift on the sea of life without paddle or rudder. Since the rules no longer apply, she’s suddenly free to engage in behaviors she would have once considered outrageous, scandalous and even blasphemous, including seducing an underage minor in the basement of the church she attends.

Admittedly, Margery is an extreme case, but playwright Robert Askins did not concoct her to explore notions of grief and guilt experienced by people in the aftermath of losing  a spouse, parent or child. For Margery’s behavior to make sense, her mindset must operate successfully on this plane. And from this framework, it’s important for the audience to accept that Margery will be stuck in the grieving process until she is able to redefine who she is and who she wants to be.

a spouse, parent or child. For Margery’s behavior to make sense, her mindset must operate successfully on this plane. And from this framework, it’s important for the audience to accept that Margery will be stuck in the grieving process until she is able to redefine who she is and who she wants to be.

With that as predicate, we’re able to perceive that Margery’s true function in Hand to God is to question the very notion that people should strive for goodness.

“So much of what we think is deeply right or wrong is simply etiquette,” Askins has stated in interviews. “State-sponsored etiquette, so the sufficiency of that is problematic. The thing that you think is good can destroy the world and the thing you think is bad can save it.”

“So much of what we think is deeply right or wrong is simply etiquette,” Askins has stated in interviews. “State-sponsored etiquette, so the sufficiency of that is problematic. The thing that you think is good can destroy the world and the thing you think is bad can save it.”

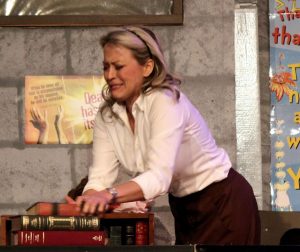

Cerebrally understanding the purpose and role that Margery fulfills in Hand to God is one thing; breathing life into a newly-nihilistic, out-of-control Southern  woman is an entirely different challenge – and not one that Sanders was predisposed to successfully portray. In previous roles, such as Minka Lipinski in Jeffrey Hatcher’s Murderers or Margery Pinchwife in The Country Wife, Sanders played women who are essentially cool, calm and collected and largely self-contained. She showed glimpses of unrestrained emotionality in The Taming, but nothing on a par with the reckless abandon she expresses in Hand to God.

woman is an entirely different challenge – and not one that Sanders was predisposed to successfully portray. In previous roles, such as Minka Lipinski in Jeffrey Hatcher’s Murderers or Margery Pinchwife in The Country Wife, Sanders played women who are essentially cool, calm and collected and largely self-contained. She showed glimpses of unrestrained emotionality in The Taming, but nothing on a par with the reckless abandon she expresses in Hand to God.

She tosses chairs and breaks furniture, rips pages from religious books and tosses them high in the air. Upset with her son’s inability to  relate to her one-on-one, she stops her car and tells him to get out and walk his ass home. F-bombs and related epithets roll off her tongue with an ease that rivals Megan Fox, Pretty Reckless lead singer Taylor Momsen and foul-mouthed Kate Winslet. Her sex scenes sizzle – and not just because she’s beautiful and has the lithe body of a dancer. “Rip open my shirt,” she demands of 17-year-old Tim-Tim after forcing him to eat a poster depicting a happy, smiling family. She wants to punish and be punished, to enjoy sex

relate to her one-on-one, she stops her car and tells him to get out and walk his ass home. F-bombs and related epithets roll off her tongue with an ease that rivals Megan Fox, Pretty Reckless lead singer Taylor Momsen and foul-mouthed Kate Winslet. Her sex scenes sizzle – and not just because she’s beautiful and has the lithe body of a dancer. “Rip open my shirt,” she demands of 17-year-old Tim-Tim after forcing him to eat a poster depicting a happy, smiling family. She wants to punish and be punished, to enjoy sex  without any risk of love. Action without judgment or consequences. She thrusts an open hand to God. Talk to the hand, God. Talk to the hand.

without any risk of love. Action without judgment or consequences. She thrusts an open hand to God. Talk to the hand, God. Talk to the hand.

Sanders has always possessed the raw talent to play a role like the one of Margery, but it took a pro like Nykkie Rizley to draw the performance out of her through a combination of out-of-the-box direction and good, old-fashioned screaming. And Rizley didn’t stop with Coe and Sanders. She also found a way to draw equally provocative performances from TJ Albertson  (who plays Timothy), Kenneth Bradley Johnson (Pastor Greg) and Sofia Weymouth (Jessica).

(who plays Timothy), Kenneth Bradley Johnson (Pastor Greg) and Sofia Weymouth (Jessica).

If you’re one of those theater-goers who’s always on the look-out for exceptional acting, Hand to God is a play you don’t want to miss. And as a side bonus, you’ll laugh your ass off. The play is as funny as it is well acted, and that’s saying a mouthful. See below for play dates, times and ticket information.

RELATED POSTS.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.