Crussard and Benzing make ‘D.M.V.’ more than mere lighthearted summer fare

On stage for the next two weekends at Lab Theater is a fascinating little play titled D.M.V. As a result of truly insightful direction from Carmen Crussard and first-rate acting by Gerri Benzing, D.M.V. transcends the status of mere lighthearted comedic summer fare to provide a rare glimpse into the plight of the 9-to-5 bureaucrat.

On stage for the next two weekends at Lab Theater is a fascinating little play titled D.M.V. As a result of truly insightful direction from Carmen Crussard and first-rate acting by Gerri Benzing, D.M.V. transcends the status of mere lighthearted comedic summer fare to provide a rare glimpse into the plight of the 9-to-5 bureaucrat.

Ah, you rightly ask, why would anyone write never lone care about the trials, tribulations and triumphs of a bureaucrat?

the trials, tribulations and triumphs of a bureaucrat?

“They are the supposedly human face of the state—cold, distant, unconcerned,” writes When the State Meets the Street: Public Service and Moral Agency author Bernardo Zacka. “Of all the ills of bureaucracy, they might be the worst. They look without seeing, they listen without hearing, and they proclaim decisions that can change people’s lives with  the indifference of a butcher slicing a piece of steak.”

the indifference of a butcher slicing a piece of steak.”

In D.M.V., this unsavory persona is embodied in the character of Bernice Hodes, who serves as the manager of a local branch of the Department of Motor Vehicles.

Ugh.

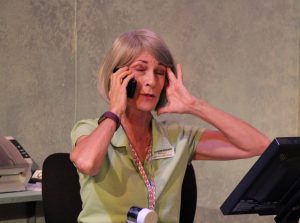

Compliments of an opening scene telephone conversation with her daughter, we quickly learn that today is Bernice’s last day.  After 30 years on the job, she’s retiring with a full pension. She’s sold her home, packed her belongings and is moving miles away to be closer to her daughter, whom she adores. Her co-workers threw her a retirement party the night before at which she apparently had a very good time, downing innumerable margaritas. Now she’s enduring a splitting headache and

After 30 years on the job, she’s retiring with a full pension. She’s sold her home, packed her belongings and is moving miles away to be closer to her daughter, whom she adores. Her co-workers threw her a retirement party the night before at which she apparently had a very good time, downing innumerable margaritas. Now she’s enduring a splitting headache and  low energy. But hey, all she has to do is get through one last shift.

low energy. But hey, all she has to do is get through one last shift.

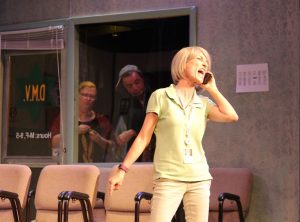

The purpose of this opening monologue is two-fold. It humanizes Bernice. She’s a loving mom, fun-loving friend and courageous woman (all attributes, incidentally, that are possessed by Gerri Benzing, who professes to be something of a daredevil, having zip-lined across canyons in Colorado and has  hang-gliding from a cliff near the top of her bucket list). But we’re simultaneously reminded that Bernice is a stickler for rules when she admonishes the growing line of customers cuing up outside that the Department of Motor Vehicles doesn’t open until 9 a.m. – and 9 a.m. means 9 a.m. and not one minute earlier!

hang-gliding from a cliff near the top of her bucket list). But we’re simultaneously reminded that Bernice is a stickler for rules when she admonishes the growing line of customers cuing up outside that the Department of Motor Vehicles doesn’t open until 9 a.m. – and 9 a.m. means 9 a.m. and not one minute earlier!

And herein lies the first kernel of Crussard and Benzing’s brilliance.  The juxtaposition of Bernice’s officious reprimand of the folks massing on the other side of the door with her convivial banter with her daughter illustrates her practiced ability to compartmentalize!

The juxtaposition of Bernice’s officious reprimand of the folks massing on the other side of the door with her convivial banter with her daughter illustrates her practiced ability to compartmentalize!

Compartmentalization, you discover, is an important coping strategy that a service-sector bureaucrat must learn if they have any hope of lasting in their job for very long.

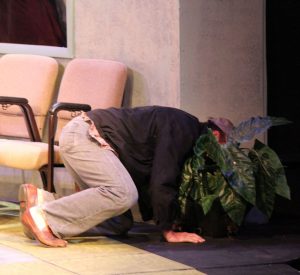

Superficially, D.M.V. seems to be more about the droll and dreadful characters who file through the waiting room and take their seat across the desk of Bernice and her trainee, Joe Hargity (played to the hilt by Sam Bostic). This, of course, is where the play derives the bulk of its farcical humor. The bank robber on the lam (Mike Dinko) who produces the ID of one dead person after another in a futile attempt

Superficially, D.M.V. seems to be more about the droll and dreadful characters who file through the waiting room and take their seat across the desk of Bernice and her trainee, Joe Hargity (played to the hilt by Sam Bostic). This, of course, is where the play derives the bulk of its farcical humor. The bank robber on the lam (Mike Dinko) who produces the ID of one dead person after another in a futile attempt  to get a current driver’s license. The 96-year-old (David Cooley) who can’t hear any better than he can see. The flask-swilling drunk (Dinko again; who else?) who barfs in a flower pot while waiting for his turn at the service desk.

to get a current driver’s license. The 96-year-old (David Cooley) who can’t hear any better than he can see. The flask-swilling drunk (Dinko again; who else?) who barfs in a flower pot while waiting for his turn at the service desk.

One character is funnier than the next; each situation more comic than the one before. In this regard, Todd Lyman is especially great.

With one exception, playwright Zalman Velvel withholds the customers’ names. They’re just numbers, which speaks volumes to the mindset of Bernice, Joe Hargity and the legion of frontline government workers they represent.

With one exception, playwright Zalman Velvel withholds the customers’ names. They’re just numbers, which speaks volumes to the mindset of Bernice, Joe Hargity and the legion of frontline government workers they represent.

But there are exceptions.

Like the mom (Margaret Cooley) with no choice but to bring her crying infant to the DMV.

It’s here that Velvel, Crussard and Benzing provide the key to understanding Bernice and, for that matter, most of the bureaucrats  who work in an office like the Department of Motor Vehicles.

who work in an office like the Department of Motor Vehicles.

“Be helpful but guard your heart,” Bernice sternly warns her trainee, Joe Hargity. “Stop that sickening sound of sympathy.”

In other words, if you give in to compassion, you’ll drive yourself batcrap crazy.

Desensitization is the adjunct to compartmentalization. They co-exist necessarily in most long-time frontline  service providers, whether they’re staffing DMV, Social Security or some other social welfare organization. It is this particular coping strategy which cloaks bureaucrats in an air of indifference. But because it’s an adaptive response to the fact that they do care, their carefully-constructed unfeeling automaton personas are

service providers, whether they’re staffing DMV, Social Security or some other social welfare organization. It is this particular coping strategy which cloaks bureaucrats in an air of indifference. But because it’s an adaptive response to the fact that they do care, their carefully-constructed unfeeling automaton personas are  often little more than a tenuous façade.

often little more than a tenuous façade.

Recognizing the fragility of her own veneer, Bernice does desensitization and compartmentalization one better. Her failsafe coping mechanism is a nearly inflexible adherence to the rules. She applies them meticulously, fairly and impartially, treating everyone identically – no matter  who they are.

who they are.

Benzing handles the rigors of bringing this aspect of her character’s personality to life with such remarkable aplomb that she often appears as a hapless straight man (or woman) caught in a vortex of revolving characters who show up with incomplete paperwork and act so confused or agitated that they cannot comprehend even the simplest instructions that she tries  to impart.

to impart.

But make no mistake. Bernice Hodes is not hapless. To the contrary, she’s the glue that holds the office together. She’s the fulcrum that gives co-workers and customers a soothing sense of order.

Shenanigans aside, these ordinary rank-and-file people understand there are rules. More, they accept that they have to follow them. Oh, they may huff and puff and threaten to blow the house down, but in the end, they abide by the rules.

But then along comes Jimmy Rogers (perfectly portrayed by Art Keen),  who’s never met a rule he couldn’t avoid, abrogate or flout. He shows up at DMV with an expired license, double parks his Lexus, and bribes the man who’s next in line to switch numbers with him right in front of Bernice. And then, making a bad situation even worse, he plays the “do you know who I am” card on her.

who’s never met a rule he couldn’t avoid, abrogate or flout. He shows up at DMV with an expired license, double parks his Lexus, and bribes the man who’s next in line to switch numbers with him right in front of Bernice. And then, making a bad situation even worse, he plays the “do you know who I am” card on her.

It’s the last straw.

For 29 years,  264 days and 1 hour, Bernice’s last line of defense between some semblance of order and batcrap crazytown is the intractable conviction that the rules apply to everyone. Without exception. Regardless of the car you drive, the balance in your bank account or the political influence you think you can bring to bear.

264 days and 1 hour, Bernice’s last line of defense between some semblance of order and batcrap crazytown is the intractable conviction that the rules apply to everyone. Without exception. Regardless of the car you drive, the balance in your bank account or the political influence you think you can bring to bear.

So Bernice places  Jimmy at the back of the line. When he persists in trying to circumvent the rules, she takes newcomers ahead of him, has his car towed, and then manipulates the reading chart so that he flunks his vision test.

Jimmy at the back of the line. When he persists in trying to circumvent the rules, she takes newcomers ahead of him, has his car towed, and then manipulates the reading chart so that he flunks his vision test.

The war between these two escalates from there, with the mayor (wonderfully played by Stacy Stauffer) and Bernice’s boss,  the tax collector (David Cooley) being called in. But even when she’s threatened with termination and loss of her pension just six hours shy of full vesting upon completion of 30 years of service (shades of Andrew McCabe), Bernice refuses to yield.

the tax collector (David Cooley) being called in. But even when she’s threatened with termination and loss of her pension just six hours shy of full vesting upon completion of 30 years of service (shades of Andrew McCabe), Bernice refuses to yield.

Ironically, in standing up to Jimmy Rogers, the mayor and even her boss,  Bernice breaks all of the rules herself! But that’s the thing. Facades, masks and barriers are not impenetrable. They can be breached; they occasionally dissolve. That typically happens because the person on the other side of the desk cracks an especially funny joke, gives a sincere compliment or finds some other way to make a personal connection. In this instance, however, it’s a combination

Bernice breaks all of the rules herself! But that’s the thing. Facades, masks and barriers are not impenetrable. They can be breached; they occasionally dissolve. That typically happens because the person on the other side of the desk cracks an especially funny joke, gives a sincere compliment or finds some other way to make a personal connection. In this instance, however, it’s a combination  of arrogance, high-handedness and Jimmy’s unapologetic sense of entitlement. But the result is the same. It evokes a genuine human reaction, that of anger, pettiness and, well, a he’s-got-it-coming good, old-fashioned smackdown.

of arrogance, high-handedness and Jimmy’s unapologetic sense of entitlement. But the result is the same. It evokes a genuine human reaction, that of anger, pettiness and, well, a he’s-got-it-coming good, old-fashioned smackdown.

You’ll have to see the show to find out how it all shakes out.  But along with the laughs and guffaws that ripple with regularity through the audience, you’ll come away with the unmistakable conclusion that D.M.V. provides novel insight into the fragmented psyche of the frontline bureaucratic government worker. And that’s due not only to the storyline provided by the playwright, but the fine job of directing and marvelous acting of Crussard and Benzing. In this, they’re aided by an amazingly accurate set (right down to the smallest details) and terrific performances rendered by the

But along with the laughs and guffaws that ripple with regularity through the audience, you’ll come away with the unmistakable conclusion that D.M.V. provides novel insight into the fragmented psyche of the frontline bureaucratic government worker. And that’s due not only to the storyline provided by the playwright, but the fine job of directing and marvelous acting of Crussard and Benzing. In this, they’re aided by an amazingly accurate set (right down to the smallest details) and terrific performances rendered by the rest of the cast.

rest of the cast.

For all of these reasons, D.M.V. is more than just a farcical comedy or lighthearted summer fare. It’s a modern day morality play that underscores that the rules of society should apply evenly to every citizen, regardless of wealth, social status or who you know.

August 14, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.