Under Annette Trossbach’s intensive direction, ‘Botticelli in the Fire’ is unqualified theatrical triumph

In the Miss Dior Eau de Parfum commercial, Natalie Portman asks pointedly, “And you, what would you do for love?” Would you sacrifice your life like Romeo or Juliet? Would you agree to be expatriated to another country as Lancelot did for Guinevere? Would you abdicate the throne as Edward VIII did for Wallis Simpson? Would you renounce your career or life’s work for the object of true love? This is the question that Sandro Botticelli is constrained to answer in Jordan Tannahill’s Botticelli in the Fire, which opens tonight at the Laboratory Theater of

In the Miss Dior Eau de Parfum commercial, Natalie Portman asks pointedly, “And you, what would you do for love?” Would you sacrifice your life like Romeo or Juliet? Would you agree to be expatriated to another country as Lancelot did for Guinevere? Would you abdicate the throne as Edward VIII did for Wallis Simpson? Would you renounce your career or life’s work for the object of true love? This is the question that Sandro Botticelli is constrained to answer in Jordan Tannahill’s Botticelli in the Fire, which opens tonight at the Laboratory Theater of  Florida.

Florida.

As the play opens, we find the incomparable Italian Renaissance master living large in late 15th century Florence, where he’s been commissioned to paint the portrait of Clarice Orsini. His benefactor is Clarice’s husband, Lorenzo de Medici, who also just happens to govern Florence. Botticelli and de Medici are close and trusted friends, but that doesn’t prevent Sandro from boinking Clarice in studio if not en plein air and then rendering her on canvas in post-coital afterglow with the collaboration of his friend Leo – as in Leonardo da Vinci. It takes just one cursory glance at the finished painting for LoD to realize that Sandro has betrayed their friendship and, worse,  the bond of trust he’d thought he’d forged with the artist. At first, de Medici threatens to return the favor and emasculate the painter. But Clarice intervenes and persuades her cuckolded husband to take away what Botticelli loves most, his young assistant, Leo. Now, Sandro must decide which is more important, the masterpieces he’s painted over the course of his illustrious career or the love of his life.

the bond of trust he’d thought he’d forged with the artist. At first, de Medici threatens to return the favor and emasculate the painter. But Clarice intervenes and persuades her cuckolded husband to take away what Botticelli loves most, his young assistant, Leo. Now, Sandro must decide which is more important, the masterpieces he’s painted over the course of his illustrious career or the love of his life.

Full stop.

Don’t get hung up on the historical accuracy of the plotline. First and foremost, the story is told from Sandro Botticelli’s perspective – and the iconic painter takes full advantage of the opportunity to burnish his brand some 500+ years after the fact (including portraying himself as the alpha to da Vinci’s beta). Secondly (but no less importantly), Jordan Tannahill is unapologetic about the “ahistorical but emotionally plausible narrative” that underpins his storyline

get hung up on the historical accuracy of the plotline. First and foremost, the story is told from Sandro Botticelli’s perspective – and the iconic painter takes full advantage of the opportunity to burnish his brand some 500+ years after the fact (including portraying himself as the alpha to da Vinci’s beta). Secondly (but no less importantly), Jordan Tannahill is unapologetic about the “ahistorical but emotionally plausible narrative” that underpins his storyline  like gesso on a swatch of newly-stretched canvas. In fact, if you’re an art history major or just a Renaissance wonk, part of the fun in watching Botticelli in the Fire is seeing how Tannahill distorted the historical record and compressed the associated timeline to extract a morality story from a backdrop of amoral hedonism and abject narcissism.

like gesso on a swatch of newly-stretched canvas. In fact, if you’re an art history major or just a Renaissance wonk, part of the fun in watching Botticelli in the Fire is seeing how Tannahill distorted the historical record and compressed the associated timeline to extract a morality story from a backdrop of amoral hedonism and abject narcissism.

But fear not. You need not have a degree in art or history to appreciate this play.  Although the characters are set in another time and place, they have an immediacy that is readily accessible to modern-day audiences. That’s because in our present selfie-dominated, look-at-me, social-media-driven culture, we all have varying degrees of Sandro Botticelli in our emotional make-up.

Although the characters are set in another time and place, they have an immediacy that is readily accessible to modern-day audiences. That’s because in our present selfie-dominated, look-at-me, social-media-driven culture, we all have varying degrees of Sandro Botticelli in our emotional make-up.

Okay, perhaps not to the extent displayed by Mondo Sandro, who rants early on ““People would come up to me at a party and they’d be just dripping with jealousy. I remember this one queen, he said to me, ‘I heard you once had an orgy with 30 people that lasted a whole weekend.’ And I was like: ‘Once?’ Please. Do  your research, girl. Do. Your. Research. ‘Once’ — cute.”

your research, girl. Do. Your. Research. ‘Once’ — cute.”

But, keeping it real, wouldn’t we all love love to be that guy?

Or a Kardashian?

Or a Real Housewife?

Or a pro athlete, celeb, entrepreneur or politician who’s so rich, so popular, so powerful that they can say or do just about anything like,  I dunno, shoot someone of Fifth Avenue, and people would turn a blind eye, if not applaud?

I dunno, shoot someone of Fifth Avenue, and people would turn a blind eye, if not applaud?

And this brings us to the crux of the matter in this Jordan Tannahill masterpiece of theater.

Ah, but could someone who is that egocentric, that self-absorbed, who is that utterly and hopelessly narcissistic ever  sacrifice the accolades, the aggrandizement and the trappings of success – not to mention a body of work that will endure for half a millennium – for another person? For love? Would they – could they – exchange “the lifestyle” for the simple pleasure of copping a squat and sharing peanut butter sandwiches on a bare wooden floor?

sacrifice the accolades, the aggrandizement and the trappings of success – not to mention a body of work that will endure for half a millennium – for another person? For love? Would they – could they – exchange “the lifestyle” for the simple pleasure of copping a squat and sharing peanut butter sandwiches on a bare wooden floor?

To be fair, that’s not the question that initially intrigued Tannahill.  His eye had fallen upon a footnote in an art history textbook that said that in 1497, Botticelli had burned a number of his paintings in the Bonfire of the Vanities at the behest of a fanatical Dominican friar by the name of Girolamo Savonarola, and he’d wondered what would have provoked an artist as accomplished as Botticelli to

His eye had fallen upon a footnote in an art history textbook that said that in 1497, Botticelli had burned a number of his paintings in the Bonfire of the Vanities at the behest of a fanatical Dominican friar by the name of Girolamo Savonarola, and he’d wondered what would have provoked an artist as accomplished as Botticelli to  do such an unthinkable thing. (Bear in mind that Botticelli’s works today routinely fetch $10 million or more at auction.)

do such an unthinkable thing. (Bear in mind that Botticelli’s works today routinely fetch $10 million or more at auction.)

Obviously, Tannahill is a romantic because he concluded that love had to be at the heart of it rather than a mind so undisciplined that it could be susceptible to populism and conspiracy theories.

Regardless of what Lab Artistic Director Annette Trossbach may have  thought about the central theme of the play, the liberties that Jordan Tannahill took with the historical record or the way that reality is filtered through the lens of the protagonist (reference her character in How to Transcend a Happy Marriage), she saw in Botticelli in the Fire “the most revolutionary theater … since Hamilton.”

thought about the central theme of the play, the liberties that Jordan Tannahill took with the historical record or the way that reality is filtered through the lens of the protagonist (reference her character in How to Transcend a Happy Marriage), she saw in Botticelli in the Fire “the most revolutionary theater … since Hamilton.”

From every conceivable angle, Botticelli in the Fire is groundbreaking. The play plumbs the depths of beauty, sensuality, lust and love, blurring the lines between these interrelated and oft-overlapping concepts with all the messiness, menace and mayhem of a Jackson Pollock abstract. Unlike The Crucible, Botticelli endears itself to present-day audiences through 21st century street vernacular, skinny jeans, cellphones, dance choreography (compliments

From every conceivable angle, Botticelli in the Fire is groundbreaking. The play plumbs the depths of beauty, sensuality, lust and love, blurring the lines between these interrelated and oft-overlapping concepts with all the messiness, menace and mayhem of a Jackson Pollock abstract. Unlike The Crucible, Botticelli endears itself to present-day audiences through 21st century street vernacular, skinny jeans, cellphones, dance choreography (compliments  of Isabel Isenhower) and original music (by Annette Trossbach and Scott Davis). The parallels between the bubonic plague that ravaged Florence at the turn of the 16th century and today’s worldwide coronavirus pandemic cannot be overhyped, including the overarching need of demagogues in every epoch to scapegoat someone, anyone (sodomites then, Jews in the 1920s and ’30s,

of Isabel Isenhower) and original music (by Annette Trossbach and Scott Davis). The parallels between the bubonic plague that ravaged Florence at the turn of the 16th century and today’s worldwide coronavirus pandemic cannot be overhyped, including the overarching need of demagogues in every epoch to scapegoat someone, anyone (sodomites then, Jews in the 1920s and ’30s,  people of Asian descent in connection with the “China virus” and members of the LGBTQ community across the ages) for the latest manifestation of Almighty God’s wrath.

people of Asian descent in connection with the “China virus” and members of the LGBTQ community across the ages) for the latest manifestation of Almighty God’s wrath.

But it’s the challenge of the never-done-before that gets Trossbach’s motor revving, and on top of everything else, Botticelli in the Fire takes on-stage intimacy to unprecedented heights.

Lab has long  had an intimacy contract. But for this production, those guidelines had to be re-examined and refined. Referred to by the shorthand appellation of “the 3 Cs,” everyone in the show practices “consent, communication and closure” not just at the time of casting or the beginning of the rehearsal process, but on a daily basis. Trossbach and company acknowledge that emotions can change in the blink of an eye, and an actor may have a problem today with something they thought they were comfortable

had an intimacy contract. But for this production, those guidelines had to be re-examined and refined. Referred to by the shorthand appellation of “the 3 Cs,” everyone in the show practices “consent, communication and closure” not just at the time of casting or the beginning of the rehearsal process, but on a daily basis. Trossbach and company acknowledge that emotions can change in the blink of an eye, and an actor may have a problem today with something they thought they were comfortable  with the day before. Especially where, as here, full nudity is on display and there are graphic depictions of both heterosexual and gay kissing and intercourse.

with the day before. Especially where, as here, full nudity is on display and there are graphic depictions of both heterosexual and gay kissing and intercourse.

In fact, this show’s production has revealed the need locally for someone to have the actor’s back in even the most seemingly innocuous circumstances. Industry-wide in both theater and film, there’s a growing recognition for the need for “intimacy coordinators” or “intimacy directors” – a designee whose job it is to protect the interests and emotional wellbeing of everyone involved when a script calls for anything as simple mere touching or as complicated as a stage kiss or  simulated sex.

simulated sex.

Any of these issues could have scuttled a show as ambitious and audacious as Botticelli in the Fire. But under Trossbach’s intensive direction, Botticelli in the Fire is an unqualified theatrical triumph.

It’s more than the world-class performances she’s elicited from her cast. It’s more than  technological advances that she’s woven into the fabric of the show with the expert assistance of Technical Director Jonathan Johnson and tech assistants Margaret Cooley, M. Weymouth and Rosie DeLeon and the video wizardry of Paula Sisk. It transcends the flourishes, modern-day references, carefully-crafted ambiguities (think Frank R. Stockton’s The Lady, or the Tiger?) and homages that Trossbach includes here, there and everywhere. (For example, she even stages a scene that evokes the agony, solemnity and heroic resignation embodied by the Pieta which, while most commonly associated with his contemporary, Michelangelo, was also rendered by Botticelli half a dozen years before the timeline of

technological advances that she’s woven into the fabric of the show with the expert assistance of Technical Director Jonathan Johnson and tech assistants Margaret Cooley, M. Weymouth and Rosie DeLeon and the video wizardry of Paula Sisk. It transcends the flourishes, modern-day references, carefully-crafted ambiguities (think Frank R. Stockton’s The Lady, or the Tiger?) and homages that Trossbach includes here, there and everywhere. (For example, she even stages a scene that evokes the agony, solemnity and heroic resignation embodied by the Pieta which, while most commonly associated with his contemporary, Michelangelo, was also rendered by Botticelli half a dozen years before the timeline of  the play).

the play).

No, what makes this production of Botticelli in the Fire a triumph of art and theater is Trossbach’s ability to assemble a team and inspire them collectively to bring her clear, unequivocal and uncompromising vision to the stage.

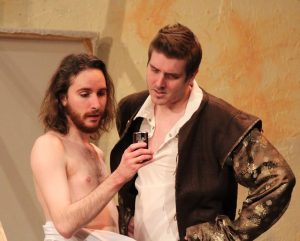

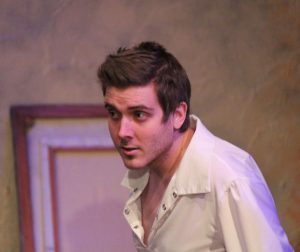

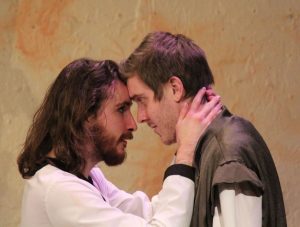

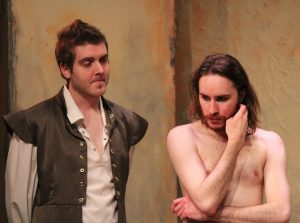

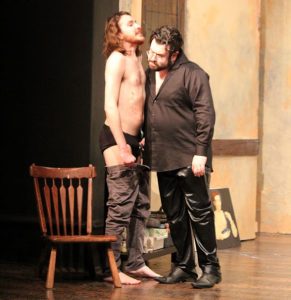

Steven Coe is too young and too good to have his performance as Sandro Botticelli characterized as “career defining.” It’s that powerful and dominant, but given the ascendancy of his vast talent, his best performances undoubtedly lie ahead. A discussion of line load and depth of emotion is certainly warranted.

But what  belies the quality of Coe’s performance is that at no time while he’s on stage will you ever be cognizant that it’s Steven Coe playing a part. He becomes and remains Sandro Botticelli and of that there can be no doubt.

belies the quality of Coe’s performance is that at no time while he’s on stage will you ever be cognizant that it’s Steven Coe playing a part. He becomes and remains Sandro Botticelli and of that there can be no doubt.

Steven Michael Kennedy’s performance is equally masterful, but so qualitatively different. What’s demanded of his character is subtlety, sensitivity and submissiveness in a physical, emotional and artistic sense. None of these adjectives  would ever be applied to describe the intellect and creative elan of the giant that was Leonardo da Vinci in real life. But keep in mind that what we know of Leo comes from the lips of Sandro Botticelli, who gets to define his friend and lover in the way that’s most flattering to Botticelli. Never mind. Kennedy is up to the challenge. For as good as he was in The Legend

would ever be applied to describe the intellect and creative elan of the giant that was Leonardo da Vinci in real life. But keep in mind that what we know of Leo comes from the lips of Sandro Botticelli, who gets to define his friend and lover in the way that’s most flattering to Botticelli. Never mind. Kennedy is up to the challenge. For as good as he was in The Legend  of Georgia McBride and Sex Tips for Married Women from a Gay Man, he’s so much better here.

of Georgia McBride and Sex Tips for Married Women from a Gay Man, he’s so much better here.

Scott Davis is chilling – and convincing – as Friar Girolamo Savonarola. In fact, he’s so despicably malevolent that the audience would no doubt break into raucous applause if they knew that about a year after the timeline in the play, Savonarola gets his comeuppance – as in being burned at the stake.

David Cooley  evokes both hatred and sympathy as the officious misogynist and vengeful husband who discovers, to his chagrin, that while hell may have no fury like a woman scorned, a woman treated dismissively may seduce your bestie just to prove a point.

evokes both hatred and sympathy as the officious misogynist and vengeful husband who discovers, to his chagrin, that while hell may have no fury like a woman scorned, a woman treated dismissively may seduce your bestie just to prove a point.

Daniel Sabiston turns in a break-out performance as the foppish Poggio di Chullu and Renee Freeman is a scene theft in her role as the wise, matronly and nurturing Madre Maria.

In  the final analysis, it’s easy to get distracted by the theatricality, technical flair, nudity and prurient sexual content of Lab Theater’s production of Botticelli in the Fire. But don’t lose sight of the show’s central premise. “And you, what would you do for love?” Or better still, what sacrifices have you made for love – for that one person in your life that purportedly means the world to you?

the final analysis, it’s easy to get distracted by the theatricality, technical flair, nudity and prurient sexual content of Lab Theater’s production of Botticelli in the Fire. But don’t lose sight of the show’s central premise. “And you, what would you do for love?” Or better still, what sacrifices have you made for love – for that one person in your life that purportedly means the world to you?

It’s no coincidence that Sandro Botticelli’s most renowned masterpiece is titled The Birth of Venus. Born of violence and blood, love and beauty blows in on a new wind, embodying the  rebirth of civilization – a new hope – a geopolitical, social and cultural shift that inevitably follows not only plague, but the celebration of ignorance and the rejection of enlightenment.

rebirth of civilization – a new hope – a geopolitical, social and cultural shift that inevitably follows not only plague, but the celebration of ignorance and the rejection of enlightenment.

It’s one of the reasons the painting has resonated with viewers for more than 500 years.

It’s one of the reasons that Botticelli in the Fire resonates with audiences today.

February 26, 2021.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.