‘Shadow Box’ underscores that terminal illness is a family affair

The Shadow Box by Michael Cristofer opens May 2 at New Phoenix Theatre on McGregor Boulevard.

The Shadow Box by Michael Cristofer opens May 2 at New Phoenix Theatre on McGregor Boulevard.

The play focuses on the lives of three terminally-ill cancer patients who are in varying stages of their final illness. Each occupies a cottage on the grounds of a hospital where they are attended not only by health care workers but their families. To defray costs, they’ve agreed to be followed and periodically interviewed by a psychologist (Jennifer Grant) for some kind of study that is never disclosed either to the patients or the audience.

either to the patients or the audience.

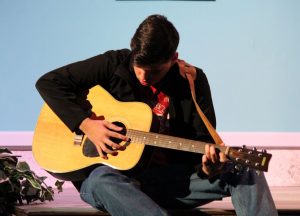

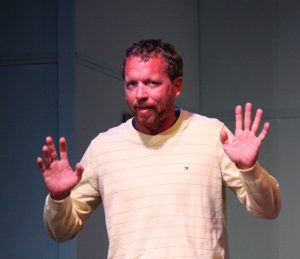

There is Joe (Grant Cothren), a working stiff who was never able to cash in on the various business and other financial opportunities that came his way before he got ill. His wife, Maggie (Amy Genzlinger), is in denial, steadfastly clinging to the unrealistic expectation that her husband will beat the odds and return home to her and their teenage son, Steve (Kagan Vann), whom mom has kept in the dark and is  therefore blissfully ignorant about his father’s impending death.

therefore blissfully ignorant about his father’s impending death.

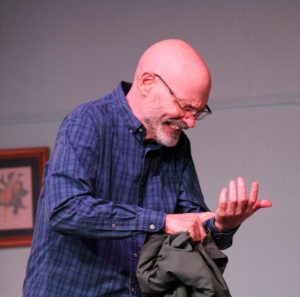

Brian (James Brock) is a garrulous philosophizer prone to quoting the Greeks and gleefully toeing the amorphous line between Apollonian order and Dionysian revelry. On the Apollonian side is Brian’s gay companion, Mark (Justin Larche). Brian’s junior by a couple of decades, Mark is resentful at being  thrust into the role of caretaker but too principled to abandon the man who rescued him from a life of pimping on the streets. Embodying the Dionysian is Brian’s ex-wife, Beverly (Joann Haley), a hard-drinking, oversexed free spirit who arrives in Brian’s cottage ostensibly to say her good-byes.

thrust into the role of caretaker but too principled to abandon the man who rescued him from a life of pimping on the streets. Embodying the Dionysian is Brian’s ex-wife, Beverly (Joann Haley), a hard-drinking, oversexed free spirit who arrives in Brian’s cottage ostensibly to say her good-byes.

Lastly, we meet Felicity (Mary Ellen Dowling), a bitter,  verbally abusive elder who is not only in end-stage cancer, but enveloped in the lengthening shadows of dementia. Her long-suffering daughter, Agnes (Sharon Isern) dotes on her every wish and whim, becoming hoist in the process on a petard of her own making much to her chagrin.

verbally abusive elder who is not only in end-stage cancer, but enveloped in the lengthening shadows of dementia. Her long-suffering daughter, Agnes (Sharon Isern) dotes on her every wish and whim, becoming hoist in the process on a petard of her own making much to her chagrin.

Since its premiere in 1977, The Shadow Box has been reviewed by a legion of theater critics. They’ve diagrammed and dissected  the plot, characters and dialogue from every conceivable angle. Although the characters’ interactions take place in a hospice for the terminally ill, wrote the New York Times’ reviewer, The Shadow Box is not about death and dying but self-realization as, according to playwright Michael Cristofer’s way of thinking, it is necessary to have an awareness of mortality

the plot, characters and dialogue from every conceivable angle. Although the characters’ interactions take place in a hospice for the terminally ill, wrote the New York Times’ reviewer, The Shadow Box is not about death and dying but self-realization as, according to playwright Michael Cristofer’s way of thinking, it is necessary to have an awareness of mortality  in order to fully understand ourselves and appreciate the lives we lead. Rather than depressing and dreary, other reviewers concluded, The Shadow Box is life-affirming, urging each of us not to take life for granted as the future is promised to no one. Yet other critics have postulated that the play’s unerring message is for each of us to be more honest, open, genuine and immediate in our relationships – now, rather than waiting for a terminal diagnosis to bring us to

in order to fully understand ourselves and appreciate the lives we lead. Rather than depressing and dreary, other reviewers concluded, The Shadow Box is life-affirming, urging each of us not to take life for granted as the future is promised to no one. Yet other critics have postulated that the play’s unerring message is for each of us to be more honest, open, genuine and immediate in our relationships – now, rather than waiting for a terminal diagnosis to bring us to  this state of self-realization and awareness.

this state of self-realization and awareness.

All of these analyses are valid and fruitful ways of interpreting the action that transpires on the New Phoenix stage. But the infirmity associated with each of these perspectives is that they focus primarily on the person who is dying. Yet, two out of every three people diagnosed with cancer have a five-year survival rate. As a result, the terminally ill and their immediate and  extended families are increasingly required to live under the specter of death for a prolonged period of time. What emerges from James Robinson’s sensitive and inspired direction of The Shadow Box is not only this realization, but the need for new templates, protocols and treatment strategies to equip terminally people and their families to navigate the murky waters of death and dying.

extended families are increasingly required to live under the specter of death for a prolonged period of time. What emerges from James Robinson’s sensitive and inspired direction of The Shadow Box is not only this realization, but the need for new templates, protocols and treatment strategies to equip terminally people and their families to navigate the murky waters of death and dying.

Through the story of Brian and Mark, Cristofer illustrates the difficulties of coping with setbacks and deterioration, as well as  the false hope created by periods of remission. The case of Agnes and her mother Felicity underscores the complexities of extended grief, which can include not only emotional fatigue, but the recriminations and self-flagellation that results from wishing that the process would just end already. And through Joe and Maggie,

the false hope created by periods of remission. The case of Agnes and her mother Felicity underscores the complexities of extended grief, which can include not only emotional fatigue, but the recriminations and self-flagellation that results from wishing that the process would just end already. And through Joe and Maggie,  we learn the lesson that denial is often premised on a couple’s inability or unwillingness to confront issues that have lain unresolved and dormant for years, if not decades only to resurface during their final days together.

we learn the lesson that denial is often premised on a couple’s inability or unwillingness to confront issues that have lain unresolved and dormant for years, if not decades only to resurface during their final days together.

In all but rare instances, the folks who comprise a terminally ill person’s support network are as much in need of counseling and coping mechanisms as the person who’s dying. The complex emotional  circumstances they’re facing can easily lead to chronic anxiety, clinical depression, PTSD and physical illness.

circumstances they’re facing can easily lead to chronic anxiety, clinical depression, PTSD and physical illness.

And then there’s the matter of financial devastation and ruin. As Joe and Maggie lament, his cancer diagnosis and treatment has cost them everything they worked their lives to amass. It may seem selfish, at first blush, for Maggie to ask what she’s supposed to do once Joe’s gone, but how does a family living paycheck to paycheck carry on in the aftermath  of a death that is compounded and confounded by the loss of home, savings and the decedent’s income?

of a death that is compounded and confounded by the loss of home, savings and the decedent’s income?

In real life, there’s a lot of Maggie in all of us. That is to say, the vast majority of people simply refuse to think or talk about the possibility of death. Yet, each of us will inevitably be thrust into a situation at some point in our lives where we must contend with the imminent loss through long-term illness of a parent, spouse, child or other loved one.

This is the magic  and strength of a production like The Shadow Box. As is the goal of all good theater, The Shadow Box can not only sensitize us to the issues we’re likely to face at that time in our lives, but start those all-important conversations with the people we love. It can also help those of us who are currently going through or who’ve previously weathered such losses to better comprehend our experiences.

and strength of a production like The Shadow Box. As is the goal of all good theater, The Shadow Box can not only sensitize us to the issues we’re likely to face at that time in our lives, but start those all-important conversations with the people we love. It can also help those of us who are currently going through or who’ve previously weathered such losses to better comprehend our experiences.

And heal.

“A life-threatening  illness has profound effects on the lives of patients, their families, and close friends,” writes cast member Sharon Isern, a 24-year cancer survivor. “Playing Agnes in The Shadow Box has brought me full circle to my life 24 years ago. It has helped me heal in ways I didn’t think possible …. Plays that make us appreciate our lives, who we are, whom we love, that help us heal, that make us feel alive [are critically important]. Because we only have this one life to live ….”

illness has profound effects on the lives of patients, their families, and close friends,” writes cast member Sharon Isern, a 24-year cancer survivor. “Playing Agnes in The Shadow Box has brought me full circle to my life 24 years ago. It has helped me heal in ways I didn’t think possible …. Plays that make us appreciate our lives, who we are, whom we love, that help us heal, that make us feel alive [are critically important]. Because we only have this one life to live ….”

Kudos are in order not only for James Robinson for his enlightened direction, but to the entire cast for fully understanding their characters and the roles they played in communicating the play’s message and overarching theme. Even though the storyline may have been structured by the playwright as a triptych, their dialogue often overlaps and each character serves as an integral part of the play’s cohesive fabric. Every single performance is noteworthy within the contours of their character. Individually and collectively, their performances merit your patronage and attendance.

Kudos are in order not only for James Robinson for his enlightened direction, but to the entire cast for fully understanding their characters and the roles they played in communicating the play’s message and overarching theme. Even though the storyline may have been structured by the playwright as a triptych, their dialogue often overlaps and each character serves as an integral part of the play’s cohesive fabric. Every single performance is noteworthy within the contours of their character. Individually and collectively, their performances merit your patronage and attendance.

May 2, 2019.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.