High time to sell the damn piano and vanquish Sutter’s ghost once and forever more

On the heels of Lab Theater’s production of Antoinette Nwandu’s drama Pass Over comes Theatre Conspiracy’s performance of August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson. Set during the Depression in Pittsburgh at the height of the Great Migration of southern African-Americans to northern cities,

On the heels of Lab Theater’s production of Antoinette Nwandu’s drama Pass Over comes Theatre Conspiracy’s performance of August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson. Set during the Depression in Pittsburgh at the height of the Great Migration of southern African-Americans to northern cities,  Wilson all-too-accurately captures the plight of blacks during the post-Reconstruction Jim Crow era where the ghost of slavery still operated to keep them “in their place” on the bottom rung of America’s economic hierarchy.

Wilson all-too-accurately captures the plight of blacks during the post-Reconstruction Jim Crow era where the ghost of slavery still operated to keep them “in their place” on the bottom rung of America’s economic hierarchy.

The Piano Lesson is incomprehensively rich in metaphors which seem even more apt and poignant in 2023  than when Wilson wrote the play in 1987. At the center of Wilson’s story is an antique piano that was acquired by a plantation owner named Sutter in exchange for two of his slaves, Boy Willie and Berniece’s great-grandmother and her son, their grandfather.

than when Wilson wrote the play in 1987. At the center of Wilson’s story is an antique piano that was acquired by a plantation owner named Sutter in exchange for two of his slaves, Boy Willie and Berniece’s great-grandmother and her son, their grandfather.

To cope with the loss of his wife and son, Boy Willie and Berniece’s great-grandfather carved their portraits and his family’s history into the piano’s face and wooden sides. The piano  took on such importance within the Charles family’s history that Boy Willie and Berniece’s father stole the piano from the Sutters one day only to be burned alive in a railroad boxcar in retaliation for the theft.

took on such importance within the Charles family’s history that Boy Willie and Berniece’s father stole the piano from the Sutters one day only to be burned alive in a railroad boxcar in retaliation for the theft.

The  last of the Sutters has just died and now Boy Willie wants to sell the piano and use his half of the proceeds of sale to buy their land and farm the property for himself rather than as a sharecropper. Berniece won’t hear of parting with the valuable family heirloom. Even though she won’t play a note on it because of the painful memories its keys invoke, to Berniece’s way of thinking parting with the piano would dishonor the sacrifices their ancestors made and be tantamount to selling their souls.

last of the Sutters has just died and now Boy Willie wants to sell the piano and use his half of the proceeds of sale to buy their land and farm the property for himself rather than as a sharecropper. Berniece won’t hear of parting with the valuable family heirloom. Even though she won’t play a note on it because of the painful memories its keys invoke, to Berniece’s way of thinking parting with the piano would dishonor the sacrifices their ancestors made and be tantamount to selling their souls.

The conflict  between Boy Willie and Berniece’s conflicting agendas ramps up over the course of the intense 2 and ½ hour story before culminating in a battle with the supernatural.

between Boy Willie and Berniece’s conflicting agendas ramps up over the course of the intense 2 and ½ hour story before culminating in a battle with the supernatural.

Boy Willie’s plans to dispose of the piano have stirred up the ghost of Sutter. As Boy Willie and his bestie, Lyman, truss up the piano and prepare to dolly it out of the house, a chill wind whips the curtains and shakes the timbers  of their Uncle Doaker’s wood frame house prompting Lyman’s romantic interest, Gloria, to declare that something ain’t right here and beat a hasty retreat out the front door. As Berniece’s boyfriend, a preacher by the name of Avery, tries to exorcise the spirit, a battle royal ensues between the ghost and Boy Willie, with the latter being repeatedly knocked down the stairs leading to the bedrooms on the second floor.

of their Uncle Doaker’s wood frame house prompting Lyman’s romantic interest, Gloria, to declare that something ain’t right here and beat a hasty retreat out the front door. As Berniece’s boyfriend, a preacher by the name of Avery, tries to exorcise the spirit, a battle royal ensues between the ghost and Boy Willie, with the latter being repeatedly knocked down the stairs leading to the bedrooms on the second floor. Sutter’s ghost only departs after Berniece begins playing the piano while frantically imploring her ancestors to drive his spirit away. Defeated, Boy Willie heads back to Mississippi empty-handed. But before departing, he admonishes his sister to keep playing the piano if she wants to hold Sutter’s ghost at bay.

Sutter’s ghost only departs after Berniece begins playing the piano while frantically imploring her ancestors to drive his spirit away. Defeated, Boy Willie heads back to Mississippi empty-handed. But before departing, he admonishes his sister to keep playing the piano if she wants to hold Sutter’s ghost at bay.

Most  people see denouement of The Piano Lesson as symbolic of the power of family love and a call to embrace rather than reject the role that slavery has played in all African-American families. While that sounds noble, it ignores the counter-argument, namely that the ghost of slavery yet operates 160 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and 58 years after the end of the Jim Crow era to relegate people of color to the lowest rung of our capitalist system.

people see denouement of The Piano Lesson as symbolic of the power of family love and a call to embrace rather than reject the role that slavery has played in all African-American families. While that sounds noble, it ignores the counter-argument, namely that the ghost of slavery yet operates 160 years after the Emancipation Proclamation and 58 years after the end of the Jim Crow era to relegate people of color to the lowest rung of our capitalist system.

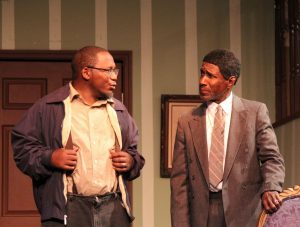

There’s no arguing that for most audience members, their sympathies lie with Berniece and her point of view, and kudos to Renee Freeman, whose performance in The Piano Lesson clearly wins the hearts of even the few folks who side with Boy Willie in their sibling conflict and rivalry. In this she’s aided by Earl Sparrow’s portrayal of Boy Willie as a pushy, unrealistic pie-in-the-sky hustler who is better suited to hawking watermelons to white folks who think they’re getting a steal. But in truth, Boy Willie is a forward-looking visionary who refuses to be saddled with the legacy of slavery.

Like it or not, the institution of slavery lies at the heart of our economic system. Even after slavery ended, law and custom operated to force African-American men, women and children to perform the dirtiest, most demeaning and lowest paying jobs. During Boy Willie’s time, this meant working as either a sharecropper or domestic servant. In fact, in several southern states, it was illegal for a black man to ply a trade or operate a business for his own account. So Boy Willie’s attempt to own his own land and operate a farm for his own account was nothing short of heroic.

Wilson wrote extensively about the Great Migration, but African-Americans who fled the south in the years following the end of World War I found that while they could escape Jim Crow, they could not escape their “caste.” In other words, they could not escape being relegated to the crummiest, crappiest jobs that white people didn’t want and often flatly refused to do.

During this time, virtually every avenue for economic independence was closed off to them. Not only was it difficult for them to own and operate a business of their own, but trade unions blocked blacks from working as plumbers, electricians and steel workers. A black man like Doaker might become a railroad conductor or cook, but never an engineer.

Even at the height of the Great Migration, 85 percent of black men and 96 percent of African-American women were employed either as sharecroppers or domestic servants. The few exceptions were preachers like Avery, teachers and small business owners who catered only to black patrons. In those rare instances where individual or communities of African Americans succeeded in attaining a modicum of financial parity, massacres like those in Tulsa (Oklahoma), Elaine (Arkansas) and Rosewood (Florida were the inevitable result.

“The historic association between menial labor and blackness served to further entrap black people in a circle of subservience in the American mind,” writes Pulitzer-Price-winning author Isabel Wilkerson in Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents.

It was this cycle of subservience that Boy Willie is trying to escape in The Piano Lesson. And he’s beaten back, put in his place, by the Sutter’s ghost – namely the remnants of a caste system built on slavery and race in which the formerly enslaved and their descendants occupied the lowest rung of the social and economic system and were condemned to a substandard life of subservience to those at the top.

God bless the genius of August Wilson. In The Piano Lesson, the Charles family escapes Sutter’s ghost by playing the piano. True that! In America, entertainment has long been the only acceptable alternative to agriculture and domestic work.

“Since the early twentieth century, the wealthiest African-Americans – from Louis Armstrong to Muhammed Ali – have traditionally been entertainers and athletes,” adds Isabel Wilkerson. “Even now, in a 2020 ranking of the richest African-Americans, seventeen of the top twenty – from Oprah Winfrey to Jay-Z to Michael Jordan – made their wealth as innovators, and then moguls, in the entertainment industry or in sports.”

So I ask you this: Did Berniece really banish Sutter’s ghost when she enlisted the aid of her ancestors – or did Sutter’s ghost leave because Berniece chose the mindset of slavery embodied by her daddy’s piano thereby sacrificing the opportunity to pursue economic opportunity, financial parity and an equal place in American society?

In the latter construction, Sutter’s ghost left because he got what he wanted – to keep Boy Willie, Berniece, Uncle Doaker and the next generation, in the figure of Maretha, in their place, namely at the bottom of the social and economic heap.

Just like Mister kept Kitch in his place by killing Moses for daring to dream of “passing over” into a life of economic opportunity and social equality.

Boy Willie was right then.

Boy Willie is right today.

It’s high time to sell the damn piano and vanquish Sutter’s ghost once and forever more.

April 21, 2023.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.