‘Boxes Are for What We Keep’ much more than a mere fish story

Boxes are for what we keep. But delve into playwright Barry Cavin’s new offering by the same name, and you’ll discover that boxes are also repositories into which we place ourselves and others. Escaping their confines is never easy. Abandoning the protection of their familiar boundaries is characteristically disquieting. For some, it may be downright unwelcome.

Boxes are for what we keep. But delve into playwright Barry Cavin’s new offering by the same name, and you’ll discover that boxes are also repositories into which we place ourselves and others. Escaping their confines is never easy. Abandoning the protection of their familiar boundaries is characteristically disquieting. For some, it may be downright unwelcome.

These are just some of the themes involved in Ghostbird Theatre  Company’s current production of Cavin’s Boxes Are for What We Keep in the screened-in Peace Pavilion at the Happehatchee Center off Corkscrew Road in Estero. Boxes consists of three short plays which enact different versions of the same fable, a simple story about two fish that are caught, held captive, and then released. One returns to the sea, but the other chooses to remain in her cage.

Company’s current production of Cavin’s Boxes Are for What We Keep in the screened-in Peace Pavilion at the Happehatchee Center off Corkscrew Road in Estero. Boxes consists of three short plays which enact different versions of the same fable, a simple story about two fish that are caught, held captive, and then released. One returns to the sea, but the other chooses to remain in her cage.

“The versions of this story, as with the Gospels, have their own turns, twists, distortions, amplifications and truths,”  says Ghostbird in A Note in their playbill. “Boxes, certainly, contain our most precious items, but they also can be prisons, comfortable coffins, hermetic enclosures, all of our own making.”

says Ghostbird in A Note in their playbill. “Boxes, certainly, contain our most precious items, but they also can be prisons, comfortable coffins, hermetic enclosures, all of our own making.”

As a playwright, Cavin’s productions are deep, multi-layered, enigmatic affairs. His love of aphorisms is surpassed only by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Cavin’s own role, as he sees it,  is to provide food for thought. Some is savory, sumptuous and thoroughly delectable. But most of the thoughts invoked by Cavin’s plays are tart, acerbic, and hard to digest.

is to provide food for thought. Some is savory, sumptuous and thoroughly delectable. But most of the thoughts invoked by Cavin’s plays are tart, acerbic, and hard to digest.

And then there’s that inevitable aftertaste. Cavin’s stories stay with you long after find your way home.

The first fish story of Boxes Are for What We Keep is a case in point.  It depicts two hillbilly fisherman by the name of Earl and Otmer, convincingly played by Terry Tincher and Jim Brock. They sit on the bank of a dark lake or river, dangling bright plastic lures from long cane poles, ultimately snaring two creatures who go by the name of Knee and Nose, played by Scott Michael and Katelyn Gravel. It turns out that Knee and Nose can not only speak, they have better command of the English language than their hillbilly captors. Otmer is hungry and wants to fry up and eat the creatures, but Earl pushes their catch into separate display boxes. Earl has a plan for

It depicts two hillbilly fisherman by the name of Earl and Otmer, convincingly played by Terry Tincher and Jim Brock. They sit on the bank of a dark lake or river, dangling bright plastic lures from long cane poles, ultimately snaring two creatures who go by the name of Knee and Nose, played by Scott Michael and Katelyn Gravel. It turns out that Knee and Nose can not only speak, they have better command of the English language than their hillbilly captors. Otmer is hungry and wants to fry up and eat the creatures, but Earl pushes their catch into separate display boxes. Earl has a plan for  his talking monsters. He intends to make a boatload of money showing off the curiosities to a string of paying customers.

his talking monsters. He intends to make a boatload of money showing off the curiosities to a string of paying customers.

As Earl and Otmer tromp into the wilderness arguing like the Stone trolls (Tom, Bert and William) from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, a winsome young girl from Trilla named Tina (played by Gabrielle Lansden) happens by. She kindly removes the lures from Knee and  Nose’s mouths. She also points out that the cages aren’t locked. Knee immediately pushes open the door to his box and escapes back into the water. But Nose hesitates, is recaptured and returned to her display.

Nose’s mouths. She also points out that the cages aren’t locked. Knee immediately pushes open the door to his box and escapes back into the water. But Nose hesitates, is recaptured and returned to her display.

Disparate messages and life lessons abound in this story. Or as Aphorism 146 from Nietzsche’s Beyond Good & Evil so aptly sums up, “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he also become a monster. And when you gaze into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.”

Say what?

To label someone a monster is to dehumanize them. To characterize an entire group or people as subhuman creates the predicate for treating them inhumanely. But history teaches that those who imprison, mistreat, abuse, torture and kill these so-called subhumans become the true monsters, and so it is that Knee and Nose come to regard their captors, particularly Earl, as worms themselves.

To label someone a monster is to dehumanize them. To characterize an entire group or people as subhuman creates the predicate for treating them inhumanely. But history teaches that those who imprison, mistreat, abuse, torture and kill these so-called subhumans become the true monsters, and so it is that Knee and Nose come to regard their captors, particularly Earl, as worms themselves.

To label someone is  fraught with other disabilities as well – not just for the person being labeled, but for the one doing the labeling. It is human nature to categorize and compartmentalize, to put people, places and things in various boxes so to speak. In Part 2 of Boxes Are for What We Keep, Cavin suggests that when we do this, we deprive ourselves of the ability to see and enjoy the subject’s true nature and beauty.

fraught with other disabilities as well – not just for the person being labeled, but for the one doing the labeling. It is human nature to categorize and compartmentalize, to put people, places and things in various boxes so to speak. In Part 2 of Boxes Are for What We Keep, Cavin suggests that when we do this, we deprive ourselves of the ability to see and enjoy the subject’s true nature and beauty.

To borrow another  aphorism from Nietzsche, “there are no facts, only interpretations.” The box into which we place people is not some objective reality. Labels such as Muslim, immigrant, liberal or conservative are just interpretations – shorthand terms that rarely reflect the full measure of the person bearing the moniker we’ve pinned on them.

aphorism from Nietzsche, “there are no facts, only interpretations.” The box into which we place people is not some objective reality. Labels such as Muslim, immigrant, liberal or conservative are just interpretations – shorthand terms that rarely reflect the full measure of the person bearing the moniker we’ve pinned on them.  It is only by getting into the water and swimming with the “monster” that we can see them as they really are.

It is only by getting into the water and swimming with the “monster” that we can see them as they really are.

Cavin incorporates this latter fish story into the fabric of Part 2 of the play through an enthralling poem that Stella Ruiz lyrically relates in her trademark sinuous, syncopated style. But the metaphor is in operation in a different fashion in an exchange that takes place between a couple named Rebekah and Abraham, played by Katelyn Gravel and Jim Brock.

Here,  we are left with the implication that just as boxes can hold heirlooms and memorabilia, our memories can serve as boxes that bind us together, but also prevent us from seeing what we and our partner have truly become.

we are left with the implication that just as boxes can hold heirlooms and memorabilia, our memories can serve as boxes that bind us together, but also prevent us from seeing what we and our partner have truly become.

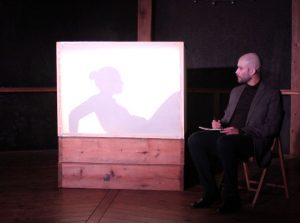

In the final segment of his trilogy, Cavin places Ruiz in a psychological box as she interacts with her therapist, played by Dan De La Rosa. The optics in this scene are incredibly powerful. Seated behind a backlit screen, all we see is Ruiz’ silhouette and that of various paper machete puppets created for the show by Caitlin  Rosolen-DeJusus. But it’s the incisive dialogue and razor-sharp repartee between Woman and Doctor that overpowers the audience, with Ruiz often turning the table and dissecting, emasculating and verbally castrating her therapist with such surgical precision that Freud himself might have been reduced to tears.

Rosolen-DeJusus. But it’s the incisive dialogue and razor-sharp repartee between Woman and Doctor that overpowers the audience, with Ruiz often turning the table and dissecting, emasculating and verbally castrating her therapist with such surgical precision that Freud himself might have been reduced to tears.

This final, penultimate scene drives home the point that the  boxes we build to hold conceptions of ourselves and others frequently do us more harm than good. They delimit, confine, even imprison us. Yet, they are so familiar and comfortable that we cling to them tenaciously – even as they lead or contribute to our ultimate demise. To live, or at least to live fully, we must cast off the boxes the circumscribe our existence.

boxes we build to hold conceptions of ourselves and others frequently do us more harm than good. They delimit, confine, even imprison us. Yet, they are so familiar and comfortable that we cling to them tenaciously – even as they lead or contribute to our ultimate demise. To live, or at least to live fully, we must cast off the boxes the circumscribe our existence.

If we don’t, we psychologically die.

This latter point was so  pivotal to Nietzsche that he promulgated not one, but several aphorisms, but his most consequential, yet least understood, is “The Honey Sacrifice” from Thus Spoke Zarathustra. “Become who you are!” Becoming who you really are requires throwing off the shackles (or boxes) that prevent you from reaching your full potential.

pivotal to Nietzsche that he promulgated not one, but several aphorisms, but his most consequential, yet least understood, is “The Honey Sacrifice” from Thus Spoke Zarathustra. “Become who you are!” Becoming who you really are requires throwing off the shackles (or boxes) that prevent you from reaching your full potential.

Boxes are for what we keep. But to achieve our full potential, we must  be willing to destroy the very boxes we construct.

be willing to destroy the very boxes we construct.

Or to borrow one final aphorism from the old German: “If a temple is to be erected, a temple must be destroyed.”

Of course, this is just a fish story, and as Cavin’s Abraham says, “Why must it mean anything?”

Ghostbird is the only  theater company in the American South devoted to site-specific work. Ever striving to partner with just the right venue for each of its productions, Ghostbird has been recognized as one of the ten best companies in Florida for live theater.

theater company in the American South devoted to site-specific work. Ever striving to partner with just the right venue for each of its productions, Ghostbird has been recognized as one of the ten best companies in Florida for live theater.

The experimental theatre company takes its name from a swamp-dwelling ivory-billed woodpecker once thought to be  extinct, but which has been spotted sporadically over the past two decades. Drawing upon the elusiveness, mystery and magic of its namesake, Ghostbird Theatre seeks to draw its audiences into those deep spiritual woods where they can discover loss, beauty, communion, reconciliation and hope.

extinct, but which has been spotted sporadically over the past two decades. Drawing upon the elusiveness, mystery and magic of its namesake, Ghostbird Theatre seeks to draw its audiences into those deep spiritual woods where they can discover loss, beauty, communion, reconciliation and hope.

RELATED POSTS.

- Terry Tincher and Dr. Scott Michael joining cast for Ghostbird’s next production

- Cavin’s ‘Boxes’ a companionable mix of black comedy and absurd theatre

- Spotlight on Terry Tincher

- Spotlight on Jim Brock

- Spotlight on Katelyn Gravel

- Spotlight on Stella Ruiz

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.