Kickin’ it with artist Marcus Jansen on virtual TGIM last night

Last night, artist Marcus Jansen was Eric Raddatz’s guest on his weekly edition of virtual TGIM. The two covered a wide range of topics, including his upcoming solo show at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Winter Park, the impact that the pandemic has had on Jansen, the meaning

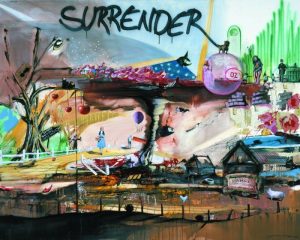

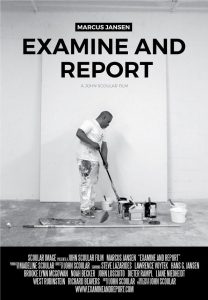

Last night, artist Marcus Jansen was Eric Raddatz’s guest on his weekly edition of virtual TGIM. The two covered a wide range of topics, including his upcoming solo show at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College in Winter Park, the impact that the pandemic has had on Jansen, the meaning  and import of his statement that “art is the most intimate act of war” and the message he seeks to convey through his urban landscape and Faceless paintings. More, the discussion provided a glimpse into the heart and soul of the artist who’s been called the most important American painter of his generation.

and import of his statement that “art is the most intimate act of war” and the message he seeks to convey through his urban landscape and Faceless paintings. More, the discussion provided a glimpse into the heart and soul of the artist who’s been called the most important American painter of his generation.

The Cornell museum show is a very big deal for Jansen. Although he has enjoyed solo museum shows in Europe, the Cornell exhibition represents the first solo museum exhibition of Jansen’s career in the United States.

The Cornell museum show is a very big deal for Jansen. Although he has enjoyed solo museum shows in Europe, the Cornell exhibition represents the first solo museum exhibition of Jansen’s career in the United States.

The Cornell Fine Arts Museum is a premier teaching and destination museum vital to the cultural fabric of the Rollins College campus and surrounding Winter Park community. The museum features rotating  exhibitions, ongoing programs, and an extensive permanent collection that spans centuries. Its holding include examples of ancient art and artifacts, European Old Master paintings (the only such collection in the Orlando area), a sizeable American art collection and a forward-thinking contemporary collection. In 1981,

exhibitions, ongoing programs, and an extensive permanent collection that spans centuries. Its holding include examples of ancient art and artifacts, European Old Master paintings (the only such collection in the Orlando area), a sizeable American art collection and a forward-thinking contemporary collection. In 1981,  the Museum became Florida’s first college museum to be accredited by the American Association of Museums (currently the American Alliance of Museums) and continues in 2020 as one of only four AAM-accredited museums in greater Orlando.

the Museum became Florida’s first college museum to be accredited by the American Association of Museums (currently the American Alliance of Museums) and continues in 2020 as one of only four AAM-accredited museums in greater Orlando.

The solo show at the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College is particularly meaningful to Jansen. He was supposed to have his first solo museum  show at the Baker Museum of Art in Naples in 2018, but was deprived of that privilege and opportunity when damage caused by Hurricane Irma in September of 2017 forced the Baker’s closure for an extended period of time.

show at the Baker Museum of Art in Naples in 2018, but was deprived of that privilege and opportunity when damage caused by Hurricane Irma in September of 2017 forced the Baker’s closure for an extended period of time.

Although not as close or convenient as the Baker Museum of Art, the Cornell Fine Arts Museum at Rollins College is only three hours away, giving local fans and collectors the opportunity to view the show, titled E Pluribus Unum, between its opening on September 18 and closing January 3, 2021.

While  many of us are going stark raving mad due to the forced isolation associated with COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and self-quarantines, Marcus told Eric Raddatz that his life has not changed all that much as a result of the pandemic.

many of us are going stark raving mad due to the forced isolation associated with COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and self-quarantines, Marcus told Eric Raddatz that his life has not changed all that much as a result of the pandemic.

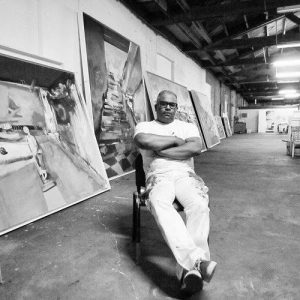

“Artists work in isolation anyway, so my [daily routine] is from  the house to the studio and from the studio back to the house each day.”

the house to the studio and from the studio back to the house each day.”

But one change he did note is in inspiration, intent and motivation.

“Where we are now, where we’re going to take the world from here, there’s great opportunity,” Marcus notes.  “I know that lots of bad things have been happening to many people, but it’s important for us to realize that this is the time for us to mold [our reality] the way we want it, not the way the oligarchs want it. I hope that resonates with people. Before

“I know that lots of bad things have been happening to many people, but it’s important for us to realize that this is the time for us to mold [our reality] the way we want it, not the way the oligarchs want it. I hope that resonates with people. Before  growth comes pain. This is our pain period.”

growth comes pain. This is our pain period.”

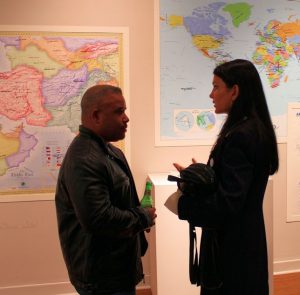

Marcus feels that it is particularly important for people from black and brown communities to appreciate the unprecedented opportunity that the pandemic and George Floyd/Black Lives Matter protests to demand systemic change “all the way from Trump on down in both parties so that this doesn’t happen again.”

But Jansen’s body of work underscores that what provides the underlying fuel for racism to flourish is economic and systematic inequality.

“Our general  economic democracy needs to come back,” Marcus told viewers during last night’s virtual TGIM. “We don’t have that.”

economic democracy needs to come back,” Marcus told viewers during last night’s virtual TGIM. “We don’t have that.”

The problem is not just that income inequality hits the poor the hardest. It’s that the higher the income inequality, the more distrustful those affected feel toward the more affluent in their community.  According to a study conducted by Elke Weber and B. Rose Huber for Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, hardship increases for low-income individuals by reducing their ability to rely on their community as a buffer against financial and other related difficulties. “This suggests that stimulus measures designed to address the economic and social fallout of the coronavirus should focus on reducing the existing income and wealth gap in our country.”

According to a study conducted by Elke Weber and B. Rose Huber for Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, hardship increases for low-income individuals by reducing their ability to rely on their community as a buffer against financial and other related difficulties. “This suggests that stimulus measures designed to address the economic and social fallout of the coronavirus should focus on reducing the existing income and wealth gap in our country.”

Citing the Princeton survey, Jansen concludes soberly that “things [like the protests and violence we are currently experiencing] are going to continue to happen because there’s a certain part of the population that simply doesn’t have the basics.”

Prescient,  Jansen has been document many of the factors that are playing out in life right now.

Jansen has been document many of the factors that are playing out in life right now.

“I speak partially from experience and partially from what I’ve observed. I’ve been watching this decline, this economic decline that we’ve been going through in this country in particular, although throughout the world. And I took it as a warning sign. It sent a sense of emergency and a sense of imminency, that we need to somehow pay attention to what’s happening. So it’s eerie because that’s exactly where we are.”

But in his  freewheeling conversation with Raddatz during last night’s TGIM, Jansen was careful to underscore that while his paintings tell stories, they are actually devoid of message.

freewheeling conversation with Raddatz during last night’s TGIM, Jansen was careful to underscore that while his paintings tell stories, they are actually devoid of message.

“My works don’t have any particular message. They’re gestural works that hopefully get people asking questions, because really my paintings are about my own questions in terms of where we are today and where we’re going. So depending on your psyche and experiences, you’re going to get a response [when you look at one of my  compositions] that you’ll be able to interpret it in your own way.”

compositions] that you’ll be able to interpret it in your own way.”

My gestural, Jansen means that when he paints, he is expressing the thoughts and emotions he is experiencing in relation to the activity he represents within the four corners of his canvas. And in this, “art is the most intimate act of war.”

“I was born in  New York City and was raised in the Bronx, which provided my first impressions of life. We later moved to Germany but I kept going back and forth between Germany and the Bronx.During the 1980s, the art there had to do with social expression, in addition to getting your name out there. And so social and political criticism became part of my genre and part of my history.”

New York City and was raised in the Bronx, which provided my first impressions of life. We later moved to Germany but I kept going back and forth between Germany and the Bronx.During the 1980s, the art there had to do with social expression, in addition to getting your name out there. And so social and political criticism became part of my genre and part of my history.”

During a stint in the military that included active duty in Iraq  during the First Gulf War, Jansen got involved in an art therapy program that provided the stimulus to pursue art as a career once he returned to the Bronx.

during the First Gulf War, Jansen got involved in an art therapy program that provided the stimulus to pursue art as a career once he returned to the Bronx.

“Art as an intimate act of war came from my own inner struggle after the Gulf War, and the transitions I had to make to painting, which I experience as intellectual and visual combat. Going back to my graffiti art days, painting has always been about social critique as a positive outlet not only for myself, but for social issues.”

One  of those issues was post-service, post-combat PTSD.

of those issues was post-service, post-combat PTSD.

“Art saved me life,” Jansen told Raddatz. “There’s no question. It wasn’t just therapeutic. It saved my life.”

It didn’t just give him a way to pay the bills doing what he loves and is passionate about. It gave him a sense of purpose.

“How fortunate it is that?”

June 2, 2020.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.