‘Walter Cronkite Is Dead’ perfect play for these times

On stage in the Joan Jenks Auditorium at the Golden Gate Community Center for two more weekends is The Studio Players’ production of Joe Calarco’s Walter Cronkite Is Dead. In the midst of yet another rancorous political season, the play provides a much-needed reminder that our dreams and disappointments unite us more than our political affiliations pull us apart. The only problem is that between COVID-19 and social media, we’re less and less likely to spend personal time

On stage in the Joan Jenks Auditorium at the Golden Gate Community Center for two more weekends is The Studio Players’ production of Joe Calarco’s Walter Cronkite Is Dead. In the midst of yet another rancorous political season, the play provides a much-needed reminder that our dreams and disappointments unite us more than our political affiliations pull us apart. The only problem is that between COVID-19 and social media, we’re less and less likely to spend personal time  with each other under circumstances that encourage us to stop, listen and understand.

with each other under circumstances that encourage us to stop, listen and understand.

But in Walter Cronkite Is Dead, Calarco gives his Margaret and Patty no easy way out. Thunderstorms up and down the east coast have grounded all flights in and out of Ronald Reagan National Airport, and Margaret has the last open table in the concourse bar. When Patty politely asks if she can join her, Margaret’s first inclination is to put her purse and reading material in the empty seat. But the normally taciturn New England progressive is too polite to turn a fellow traveler away. So she makes room for the garrulous Southern conservative  and a floodgate of rambling conversation ensues that resembles a slow-motion Paso Doble or the early rounds of a heavy weight prize fight.

and a floodgate of rambling conversation ensues that resembles a slow-motion Paso Doble or the early rounds of a heavy weight prize fight.

It quickly becomes apparent that each woman at that little airport table has preconceived notions about what the other is like. Patty assesses her tablemate as a bleeding-heart liberal while Margaret dismisses Patty as a provincial, narrow-minded Southerner  more at home at a tractor-pull than an art gallery or concert hall. But Patty quickly disabuses Margaret of that notion when she tells Miss Priss that she’s on her way to London to see a performance of Lion King because the Brits are better actors than Americans are. Margaret, by contrast, is not as forthcoming. To the contrary, she cements Patty’s – and the audience’s – presumptions by disclosing that her love of everything

more at home at a tractor-pull than an art gallery or concert hall. But Patty quickly disabuses Margaret of that notion when she tells Miss Priss that she’s on her way to London to see a performance of Lion King because the Brits are better actors than Americans are. Margaret, by contrast, is not as forthcoming. To the contrary, she cements Patty’s – and the audience’s – presumptions by disclosing that her love of everything  Kennedy inspired her to name each of her four children after various Kennedys. In fact, she named her last-born and favorite child Bobby, “because he would have made difference, don’t you agree?”

Kennedy inspired her to name each of her four children after various Kennedys. In fact, she named her last-born and favorite child Bobby, “because he would have made difference, don’t you agree?”

At this point, these two women would typically retreat into their reading material, convinced that the other wasn’t worth their time. But neither Margaret nor Patty has the  temperament or constitution to leave well enough alone, particularly Patty, who has visited every state in the Union with the exception of Hawaii. Along the way, she proudly proclaims, she’s talked to all kinds of people and nearly come to blows with those who don’t worship as she does. In fact, at one point Margaret’s undisguised disapproval and unapologetic condescension become so palpable that Patty launches into a well-deserved tirade denouncing the superior

temperament or constitution to leave well enough alone, particularly Patty, who has visited every state in the Union with the exception of Hawaii. Along the way, she proudly proclaims, she’s talked to all kinds of people and nearly come to blows with those who don’t worship as she does. In fact, at one point Margaret’s undisguised disapproval and unapologetic condescension become so palpable that Patty launches into a well-deserved tirade denouncing the superior  attitude eastern urbanites level against Middle America. And to her credit, Margaret grudgingly acknowledges the truth of Patty’s accusation.

attitude eastern urbanites level against Middle America. And to her credit, Margaret grudgingly acknowledges the truth of Patty’s accusation.

These two seem at loggerheads, but then something momentous happens that reminds them that while they may be Northerner/Southerner, progressive/conservative, Big City Mouse/Country Mouse, they are first and foremost mothers.  And as mothers, they have hopes, dreams, disappointments and tragedies the other can understand and empathize with … particularly as the carafe of wine they’re sharing lowers Margaret’s defenses and loosens her emotional armor. That commonality leads to another and then another, and they begin to forge a momentary friendship that is built on mutual respect, understanding and, yes, even admiration.

And as mothers, they have hopes, dreams, disappointments and tragedies the other can understand and empathize with … particularly as the carafe of wine they’re sharing lowers Margaret’s defenses and loosens her emotional armor. That commonality leads to another and then another, and they begin to forge a momentary friendship that is built on mutual respect, understanding and, yes, even admiration.

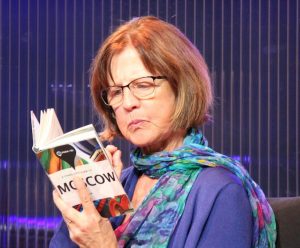

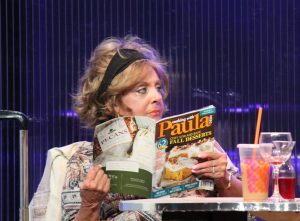

Cindy Hile and Kathleen Barney are perfect in their respective roles.  More, they’re wonderful together on The Studio Players’ stage. Not only do their roles come with a considerable line load, there’s not much on-stage action to help out by way of memory cues. But the play compensates for the lack of physical action and props by enabling the actors to give a mini-master class in facial expressions and body language. Hile, for one, could certainly qualify as a poster child for disapproval and condescension. Barney, on the

More, they’re wonderful together on The Studio Players’ stage. Not only do their roles come with a considerable line load, there’s not much on-stage action to help out by way of memory cues. But the play compensates for the lack of physical action and props by enabling the actors to give a mini-master class in facial expressions and body language. Hile, for one, could certainly qualify as a poster child for disapproval and condescension. Barney, on the  other hand, could star in a PSA that warns parents that if you let your youngster prattle on and on they’re liable to become an adult who could carry on a conversation with a fruit bowl.

other hand, could star in a PSA that warns parents that if you let your youngster prattle on and on they’re liable to become an adult who could carry on a conversation with a fruit bowl.

What’s remarkable is the chemistry they’ve achieved notwithstanding the restrictions imposed on the rehearsal process by COVID-19 and the fact that Barney came to production mid-stream to replace an actor  who found it necessary to drop out of the show over COVID concerns. But it’s clear that Hile and Barney enjoy being on stage together and their affinity for one another makes their encounters as believable as they are entertaining

who found it necessary to drop out of the show over COVID concerns. But it’s clear that Hile and Barney enjoy being on stage together and their affinity for one another makes their encounters as believable as they are entertaining

“We just hit it off and we like each other in real life,” Barney shares. “It just seemed easy to create that  chemistry.”

chemistry.”

It also helped immensely that “these are real people, and the dialogue is true to life,” adds Hile.

“What makes this play so timely and essential is that these women listen to each other,” states Director Hollis Galman in her Director’s Notes. While it’s impossible not to walk away from a performance of Walter Cronkite Is  Dead without thinking about how we could cut through our polarized political discourse if we’d just take the time to get to know one another, the show is amenable to other, deeper interpretations. Among these ancillary themes are the old adage cautioning against judging a book by its cover, the wry observation that God provides us with children so that death won’t come as such a disappointment (this one comes compliments

Dead without thinking about how we could cut through our polarized political discourse if we’d just take the time to get to know one another, the show is amenable to other, deeper interpretations. Among these ancillary themes are the old adage cautioning against judging a book by its cover, the wry observation that God provides us with children so that death won’t come as such a disappointment (this one comes compliments  of Evelyn in Two and a Half Men) and lips drink water, hearts drink wine (which is classic E.E. Cummings).

of Evelyn in Two and a Half Men) and lips drink water, hearts drink wine (which is classic E.E. Cummings).

“Through real communication, which is sometimes painful and awkward, these characters emerge as better people, through their honest exchange of ideas and feelings,” Galman suggests.

“We learn something about each other and ourselves,” Hile agrees.

In this day and age, people attach a highly negative connotation to differences of opinion and disagreements. Yet, they’re essential to helping us challenge the assumptions, presumptions and beliefs we hold. As any gym rat knows, discomfort and pain are necessary for growth, and you cannot grow as a person unless you’re able and willing to push through old, ill-conceived thoughts and

In this day and age, people attach a highly negative connotation to differences of opinion and disagreements. Yet, they’re essential to helping us challenge the assumptions, presumptions and beliefs we hold. As any gym rat knows, discomfort and pain are necessary for growth, and you cannot grow as a person unless you’re able and willing to push through old, ill-conceived thoughts and  views.

views.

But it’s not just differences and disagreements that can serve as the springboard for personal growth. Encountering people who are not at all like us gives us a template for other, perhaps more successful, approaches to problem solving and ways of being. We seem to know this intuitively in our teens and early adulthood, but we tend to become entrenched in our views and beliefs when we attain a certain age (you pick the milestone that  works best for you).

works best for you).

“I’m loud, I’m obnoxious,” says Barney of her character. “And maybe [Margaret’s] thinking I should be a little more like her” – a little more outgoing and willing to meet people halfway.

But Galman cites forgiveness as perhaps the play’s most profound message.

“[Margaret and Patty] don’t agree on a lot. Yet, through their disagreements, they’re able to forgive themselves and then each other.”

“[Margaret and Patty] don’t agree on a lot. Yet, through their disagreements, they’re able to forgive themselves and then each other.”

Walter Cronkite is Dead not only marks Galman’s directorial debut, but the first production mounted at The Studio Players Theater since COVID-19. As luck would have it, not only does it allow for easy social distancing (two characters sitting several feet apart separated by a table), it addresses the political climate in a way that no one could have anticipated pre-COVID, when this play was originally scheduled to open.

The  production is worth seeing even in a world dominated by the risk of infection. The cavernous Joan Jenks Auditorium is easily amenable to social distanced seating. The Studio Players have implemented other measures to protect their patrons and staff. And at roughly ninety-minutes plus a 15-minute intermission, you’ll be inside for less than two hours.

production is worth seeing even in a world dominated by the risk of infection. The cavernous Joan Jenks Auditorium is easily amenable to social distanced seating. The Studio Players have implemented other measures to protect their patrons and staff. And at roughly ninety-minutes plus a 15-minute intermission, you’ll be inside for less than two hours.

The play runs through October 11. See below for remaining play  dates, times and ticket information.

dates, times and ticket information.

September 28, 2020.

RELATED POSTS.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.

Tom Hall is both an amateur artist and aspiring novelist who writes art quest thrillers. He is in the final stages of completing his debut novel titled "Art Detective," a story that fictionalizes the discovery of the fabled billion-dollar Impressionist collection of Parisian art dealer Josse Bernheim-Jeune, thought by many to have perished during World War II when the collection's hiding place, Castle de Rastignac in southern France, was destroyed by the Wehrmacht in reprisal for attacks made by members of the Resistance operating in the area. A former tax attorney, Tom holds a bachelor's degree as well as both a juris doctorate and masters of laws in taxation from the University of Florida. Tom lives in Estero, Florida with his fiancee, Connie, and their four cats.